Before the war, the Czechs lived hand in hand with the Germans. Thank God that is the case again today.

Download image

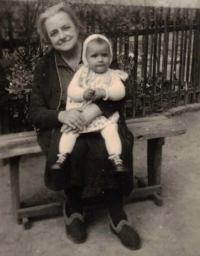

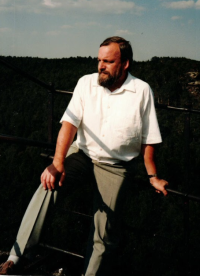

Gerhard Simchen was born on 2 July 1945, just a few weeks after the end of the Second World War, in the village of Zschepplin near Leipzig. However, his father’s family roots are in the northern Bohemian town of Filipov. His father joined the Wehrmacht as a Sudeten German and was not allowed to return home from American captivity. Gerhard’s grandparents were also deported to the Soviet occupation zone of Germany. Gerhard grew up in Ebersdorf on the German side of the historic border between Bohemia and Lusatia, essentially within sight of his father’s birthplace. During his childhood, the German Democratic Republic and the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, two supposedly friendly states from the “socialist camp”, were separated by an impenetrable border with regular border patrols and barbed wire, quite similar to the Iron Curtain of the time. This state of affairs lasted until the construction of the Berlin Wall in the early 1960s. In August 1968 Gerhard saw with his own eyes tanks of the “brotherly” armies driving across the border to occupy Czechoslovakia. Today, Mr Simchen is glad that the Czech-German border is only symbolic and that relations between Germans and Czechs are once again as smooth as they were before the war. And that he is once again free to travel whenever he likes to the country from which his ancestors were expelled. This testimony was recorded with the support of the German-Czech Future Fund.