Nowhere is it written that history cannot repeat itself.

Download image

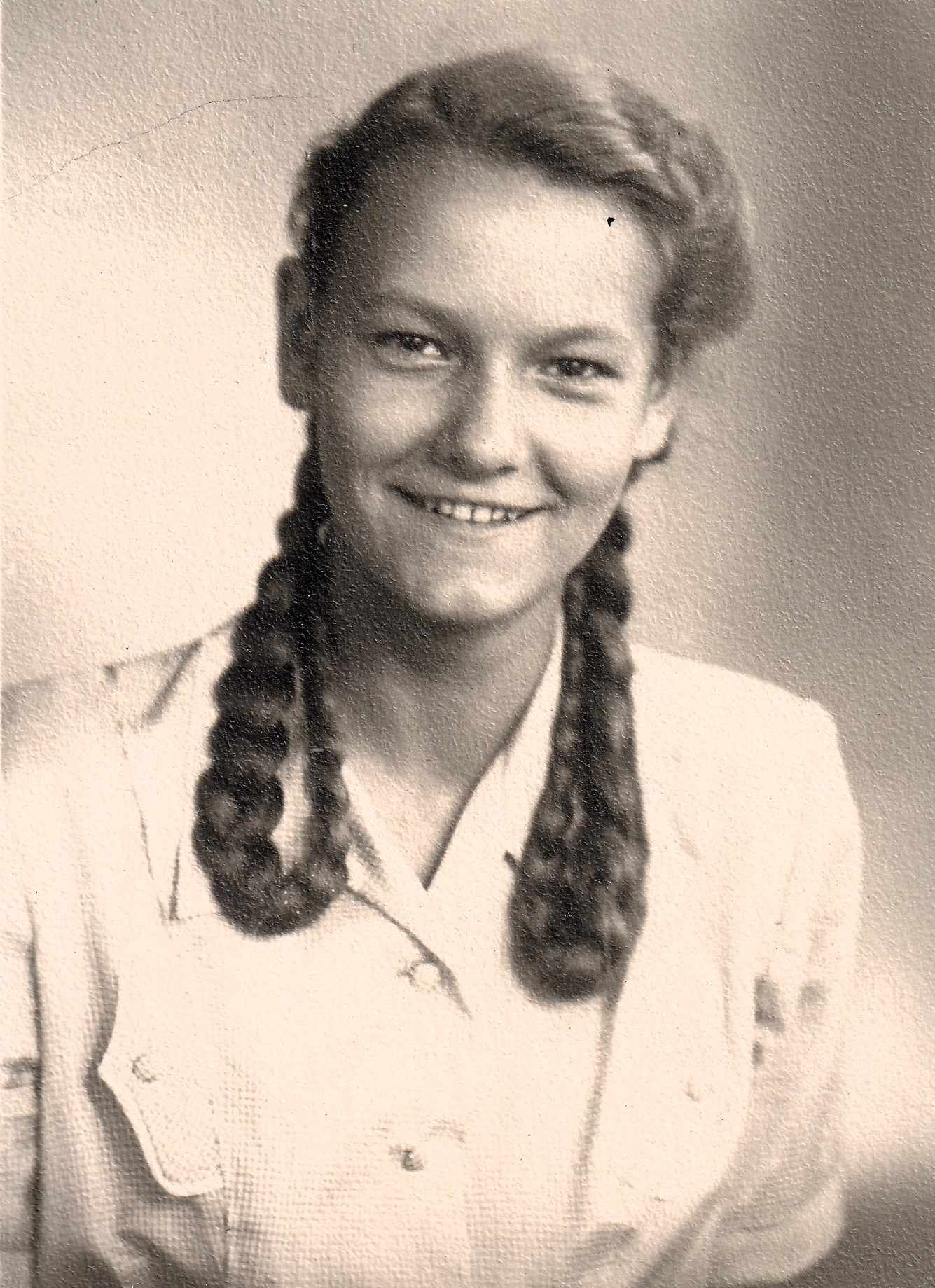

Hana Seyčková, née Petrášová, was born on 31 August 1934 in Louny as the first-born daughter of Josef Petráš and Růžena Petrášová. Her childhood was marked by the events of the late 1930s. After the Munich Agreement, the family was forced to leave their home in Ervěnice in the Sudetenland and later found a new home in Ruzyně near Prague. During the World War II, she experienced the bombing of Prague and the dramatic days of its end, when she witnessed the arrival of General Vlasov’s troops. After the war, she embarked on a career as a teacher - she graduated from the Faculty of Education and began working as a teacher. Later she moved professionally into the field of computer technology when she joined the computer centre of the State Research Institute of Thermal Technology. She further expanded her professional profile by studying mathematical informatics at the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics of Charles University (MFF UK). In 1956 she married Jiří Seyček and together they started a family. In the mid-1960s they spent several years in Ghana, where her husband worked as a civil engineer on the construction of a dam. After returning to Czechoslovakia, the witness became involved in the Ministry of Education, where she was involved in introducing computer technology into schools. Her critical views came into conflict with the new party line during the normalisation period, which led to her expulsion from the Communist Party. In the early 1980s she travelled abroad again - this time to Baghdad, where her husband was again sent on a professional mission. She welcomed the Velvet Revolution in 1989 with joy and hope for a better future. In 2025, Hana Seyčková lived in Prague-Chodov.