I was the only child in the Trutnov concentration camp

Download image

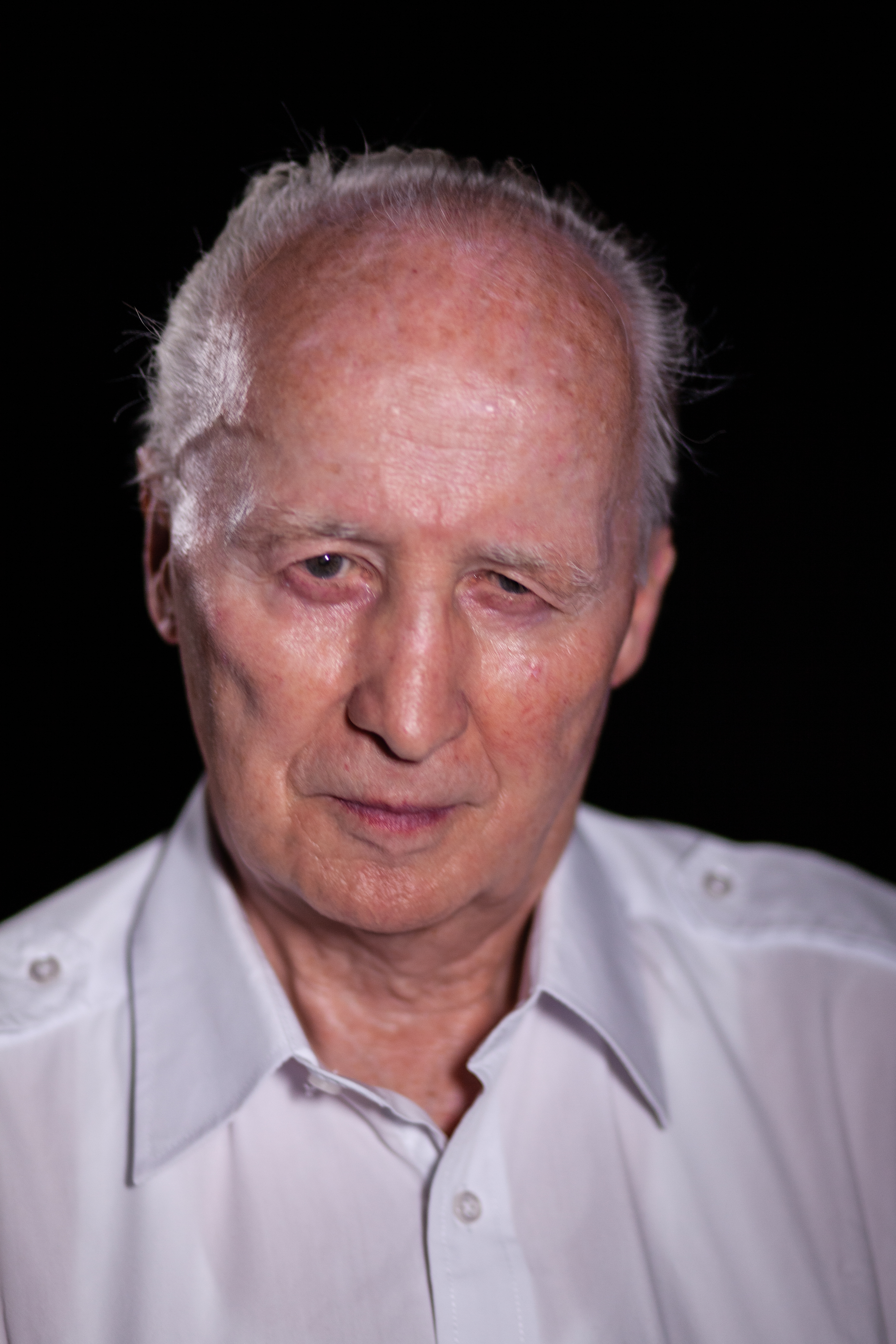

Konrad Micksch was born on 16 December 1938 in Liberec, but after his mother’s death he grew up with his aunt and grandfather in Horní Maršov. His father Franz wandered around the world as a travelling salesman, his grandfather had a pub in Maršov, where Czechs and Germans would meet. His grandfather was also a member of the town council representing the German inhabitants. From May 1945, Konrad experience several unpleasant events including an incident with Soviet soldiers in their pub. Initially in July 1945, a Czech manager was assigned to their pub, in August they experienced expulsion first-hand. They were transferred to the former concentration camp in Horní Staré Město (Upper Old Town) of Trutnov. Konrad was the only child under fifteen to be interned there. People from the camp were selected for work. One day his aunt was also chosen, so Konrad went with her to work at the Maršov II farm. A while later his grandfather managed to get him moved to their uncle’s in Svoboda nad Úpou. This uncle owned a bakery there and was already looking after Konrad’s brother. In Svoboda, Konrad also attended a Czech school, but understood almost nothing there. In the end even the baker’s family was expelled, to a former textile plant in Mladé Buky. There he once more met his grandfather and aunt. A few weeks later, the family was deported from there to the Soviet occupation zone of Germany, near Gera. Here Konrad continued with his school studies and in 1946, after five long years, he met his father who had fought in the Wehrmacht. After graduating secondary school, Konrad Micksch entered the East German army, distance studied electrical engineering and later business administration at the Dresden University of Technology. He entered the East German Communist Party (SED) and from 1961 he was employed at the Elektroprojekt manufacturing company, administering projects for power stations and other facilities, including abroad. Since 2013 he has enjoyed frequently returning to the Czech Republic.