I threw the Soviets and the Germans into the same grave

Download image

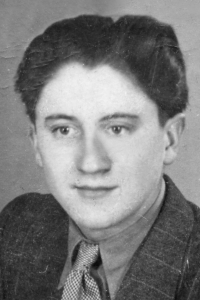

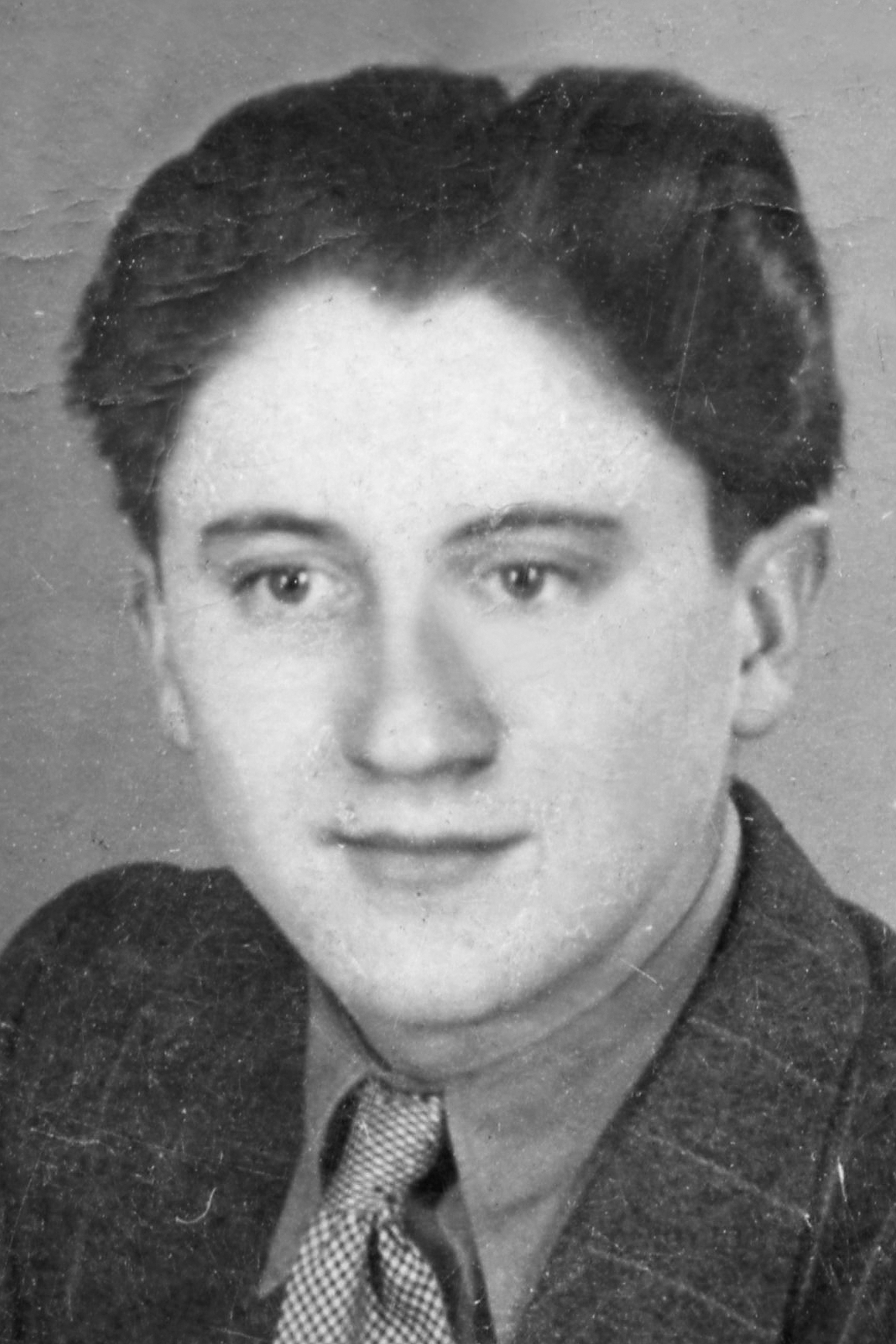

Jiří Jaroš was born on 19 March 1929 in Opava to Marie Jarošová and Bedřich Jaroš. After the death of his mother, he and his sister followed their father, a railway pointsman, to Annaberg, Germany, where he attended a German school. During the war, as a teenager, he was deployed to forced digging of anti-tank trenches. His father almost lost his life after two military trains collided. In January 1945, the Jaroš family fled the bombed-out Annaberg and hid with relatives in Chabičov in Silesia, where they lived to see the end of the war. Here, he experienced the crossing of the front and the arrival of the Red Army. Together with a friend, he was given the task of burying fallen soldiers and dead horses. He went by bike to Opava, which he found destroyed and still smouldering. After the war, he finished his education, trained as a salesman and worked his way up to manager of a hardware shop. In 1950 he started his military service at the engineers army, where he suffered serious injuries and refused an offer to cooperate with the counter-intelligence. After the death of his father, he married in 1953 to be able to take care of his younger brother. In 2025 he was living in Vršovice, Opava region.