I always attached more importance to education than to sports. I still considered football as entertainment

Download image

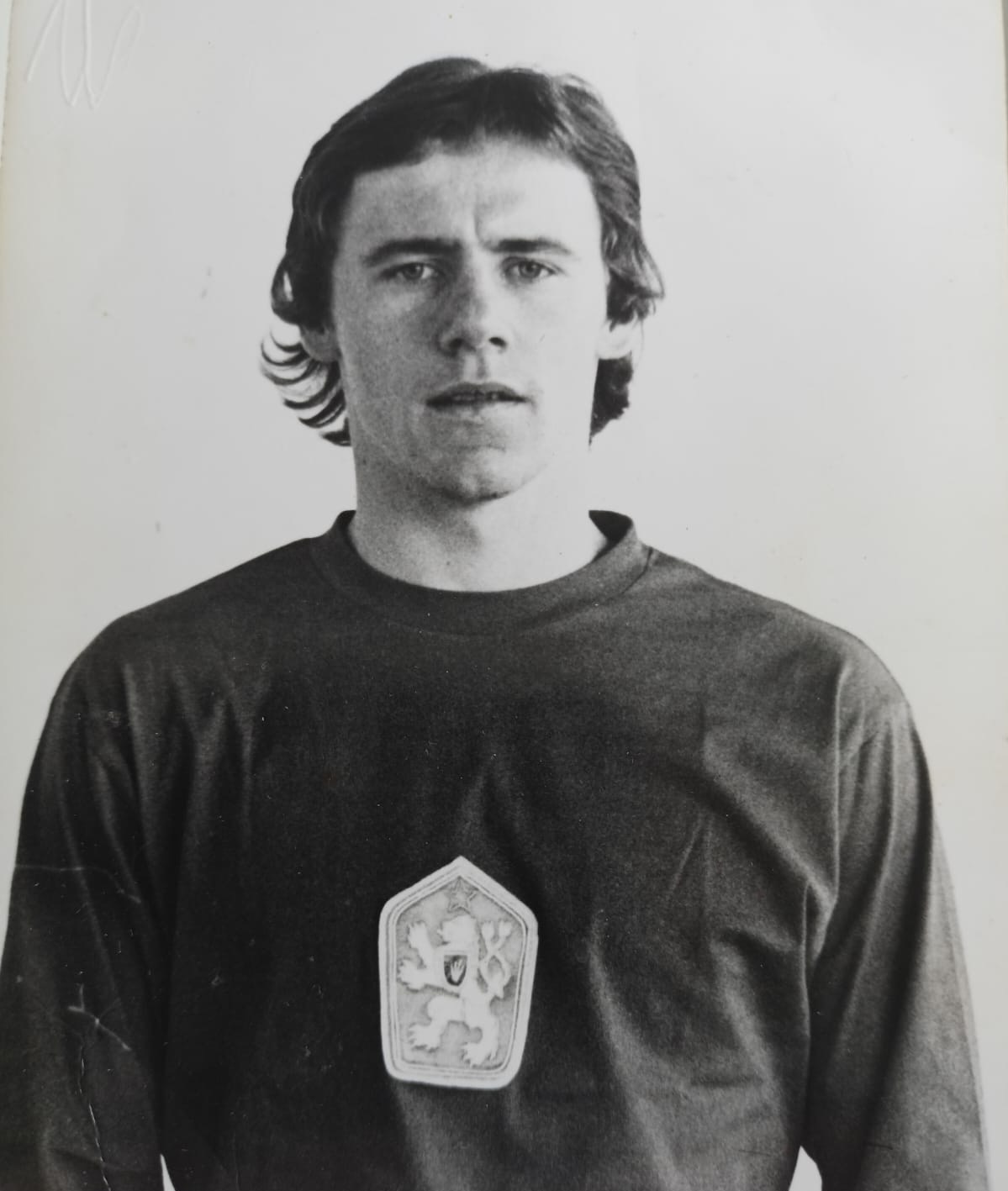

Igor Frič was born in 1956 in Ružomberok to a peasant-worker family. His parents and grandparents came from Liptovské Sliačy. His grandfather Ján Priesol was a large farmer, he smuggled horses from Poland. He had ten children. Germans and Russians lived with him, he also hid partisans. He did not voluntarily join the cooperatives. He lost thousands when changing money. His father Štefan Frič was first a foreman in the North Slovak pulp and paper mills, later a manager in the administration. He was a member of the Communist Party. His mother Jolana, née Priesolová, was a clerk. He has an older sister Soňa and a younger brother Ota. He graduated from the gymnasium in Ružomberok, graduated in Žilina. He graduated from the Transport University in Žilina. He started playing football towards the end of primary school. As a junior he played for BZVIL Ružomberok. In his youth he transferred to ZVL Žilina. He also played in the Czechoslovak youth team. He also joined Sparta Prague, from where he left due to a fractured collarbone. During his basic military service, he was first in Dukle Banská Bystrica, later in VTJ Tábor. He married Janka Fričová in 1980, had his first son Tomáš and moved to Bratislava. From 1981 to 1986, he played as a striker in CHZJD Slovan Bratislava and was managed as an employee of the Juraj Dimitrov Chemical Works. At the end of his football career, he represented BZVIL Ružomberok in 1986 - 1988. At the same time, he worked as a deputy director at the Secondary Vocational School in Ružomberok. He said goodbye to football as a youth coach of SCP Ružomberok. After the Gentle Revolution, which he welcomed and also participated in the general strike, he became the chief controller of the Ružomberok City Hall for 25 years. Today he is retired and plays sports. He has three children and lives in Ružomberok.