From beneath Parukářka, it was broadcast to the world via cables

Download image

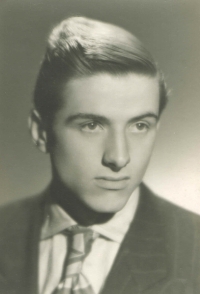

Pavel Dukát was born on 5 December 1934 in Prague. His father Emil Dukát, a senior clerk at the Main Post Office, fought as an Italian legionnaire in 1918 at the Battle of Doss Alto. Pavel witnessed the dramatic moments of the Nazi occupation in his early childhood - the mobilisation in 1938, the parade with tricolours on 28 October 1939 and the atmosphere after the assassination of Heydrich in June 1942. At the age of ten he experienced the air raid on Prague on 14 February 1945 and later became actively involved in the Prague Uprising, during which he taped over German signs and helped build barricades. In the summer of 1945, he went to his first scout camp, after which the family moved to Jablonné v Podještědí as part of the settlement of the borderlands, where his father took over the administration of the post office and became politically involved as a member of the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party. In 1948, he took part in the XI All-Sokol Meeting in Prague, then his father lost his post as headmaster and only by chance avoided a political trial in which his friends were convicted. After studying at the Faculty of Transportation of the Czech Technical University, Pavel Dukát started his military service, where he was briefly recruited by the counter-intelligence to cooperate as an informant. After the war, he joined the State Institute of Transport Design, and later worked at the Long Distance Cable Administration. In 1968 he was very involved in the Prague Spring, signing the Two Thousand Words manifesto, founding a branch of the Society for Human Rights, and watching the Soviet invasion from the Czechoslovak Radio building. He paid for it during the political checks in 1970 and has since worked in the field as a construction manager, ironically with top secret clearance. In 1982, during the construction of a long-distance cable network in Rozvadov, he met his West German colleague Norbert Fuhrmann, whose visits to Prague brought him into the focus of State Security (StB) in 1986. He experienced the Velvet Revolution with enthusiasm, participating in anti-regime demonstrations and taking part in the organisation of the general strike in Spořilov. In 2024 he was living in Prague.