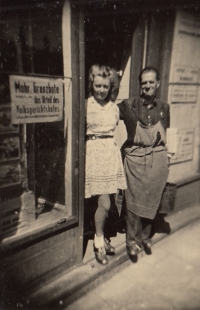

if the mother had signed, my brother could have live

Download image

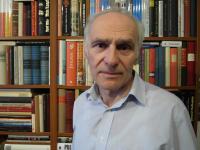

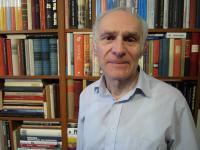

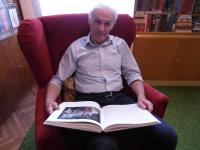

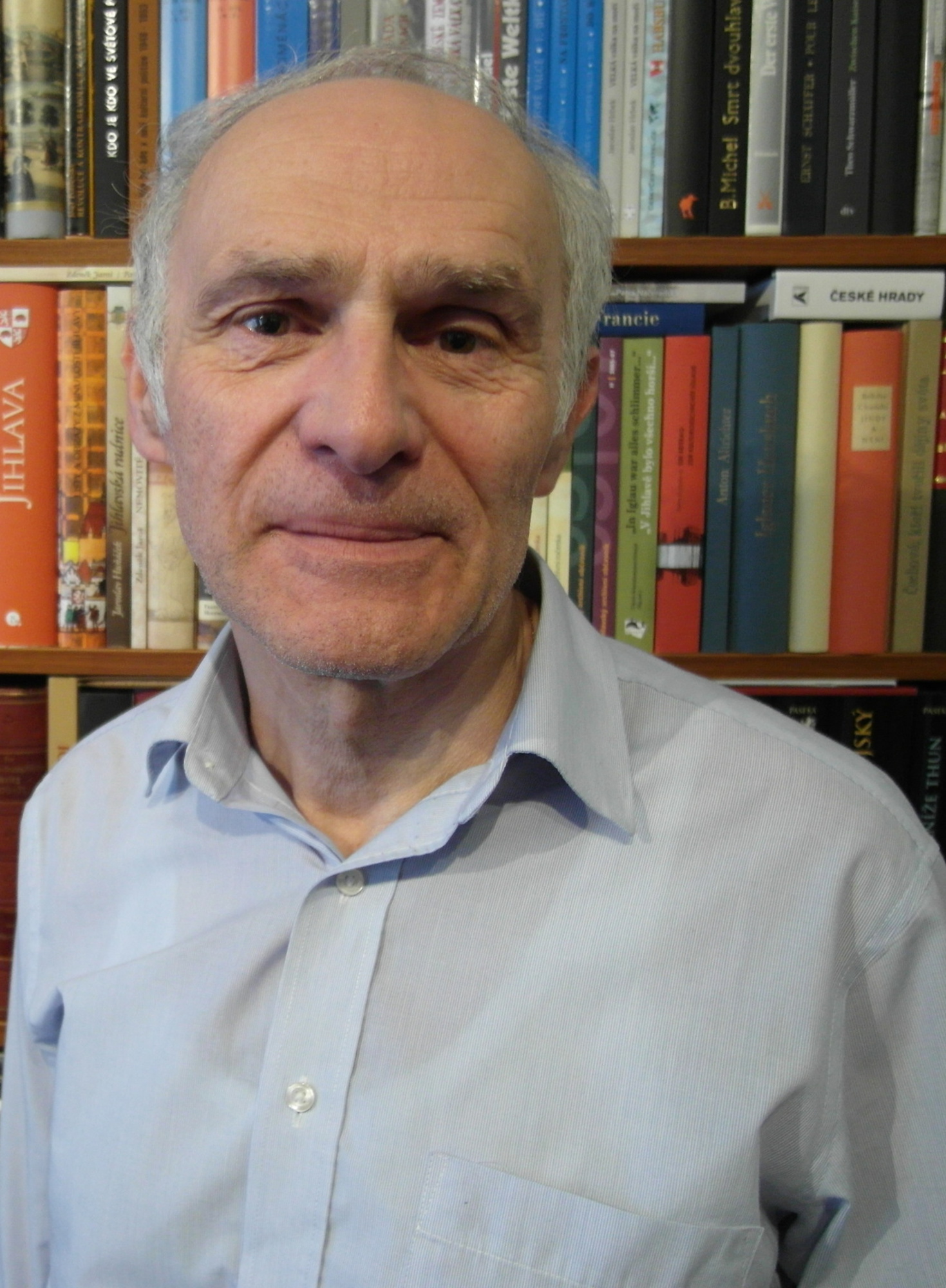

Vilém Wodák was born on 27 August, 1951 in Jihlava, that is after the WW2 was over. Despite that he mainly talks about the Czech and German relations regarding his mother´s fate. Marie Viktorie Medová, first married as Schützová, later Wodáková, was Czech. Her first husband belonged to Germans in Jihlava. He never came back from war. Marie Schützová as a person from mixed marriage was displaced together with other Germans in June 1945 and had to walk with her eighteen month old son Ewald to the Austrian border. Then she searched for her relatives in Vienna. Yet her son Ewald died due to poor post-war conditions. Thanks to her family Marie Viktorie returned to Jihlava. She married again to Vilém Wodák. Their first son, also Vilém, graduated from elementary school in 1966. Then he apprenticed and worked in rasper factory Tona. There he met Pavel Novák and due to him also the Chart 77 materials. Nowadays Vilém Wodák is active in the Association for the old Jihlava. He is dedicated to research activities.