Horničina, i když je nebezpečná a špinavá, je krásná práce s přírodou starou miliony let

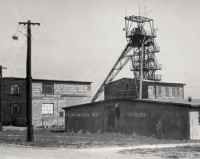

Pavel Vinkler was born on the 27th March of 1962. He spent his childhood in Dolní Rožínka where his father had moved for work. His father came from a family of farmers that lived near Hlinsko in Bohemia; they had to surrender their estate to the Unified Agricultural Cooperative. He thus accepted a metalworking job in the newly opened uranium mine at the Rozna deposit. Pavel grew up in a region which gained its charakter from mining. After having graduated from secondary school in Bystřice nad Pernštejnem, he went to study at the Technical University in Ostrava. In 1984 he graduated in Deep Mining of Uranium Deposits and found employment in his hometown at the Uranové Doly [Uranium Mines] Horní Rožínka company. From 1986, he worked as a production engineer, his job was to manage driving and transport of the extracted ore. Five years later, he became the head engineer of the mines and the head of the disaster relief service. He spent all his working life at the Rozna I shaft where he was the head engineer. The R1 shaft, on whose excavation his father worked, Pavel closed in 2017 afte sixty years of operation, when he coordinated the sad ceremony of the last cart.