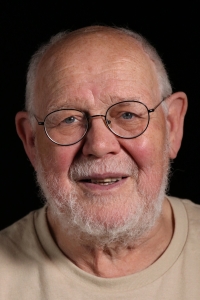

Everything you say is interesting. So say it and we’ll figure something out together

Download image

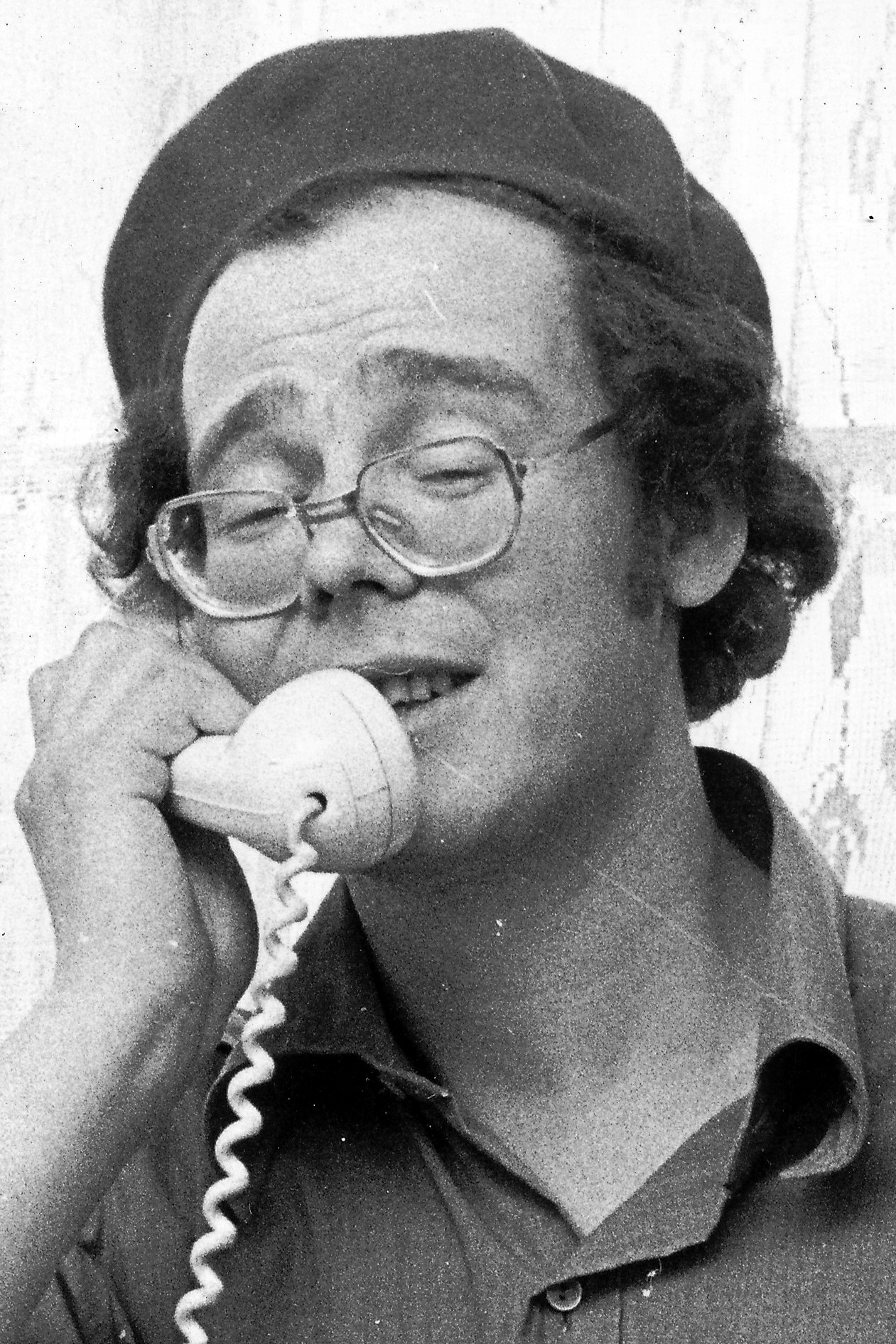

Jaroslav Veis was born on 19 January 1946 in Prague as the elder of two sons of Milada and Jaroslav Veis. He grew up in Vršovice. He graduated from grammar school and studied journalism at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University. Before November 1989, he refused to work in any newsroom. He prepared a column popularising science in the children’s magazine Sedmička pionýrů, wrote popular science articles for other periodicals and helped authors who were not comfortable with the regime to publish articles under their own or other names. Together with the dissident and later Charter signatory Alexander Kramer, he began writing science fiction stories and became an award-winning author. He translated English literature and expert articles. He socialised with dissidents. He was repeatedly interrogated by the State Security, which kept a file on him. From 1990 to 1993 he worked at Lidové noviny newspaper and was its editor-in-chief. Later, he worked as an advisor to Senate President Petr Pithart.