The Soviet invasion was a huge setback for the economy

Download image

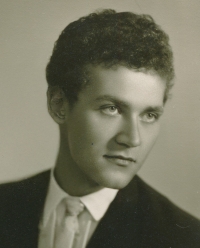

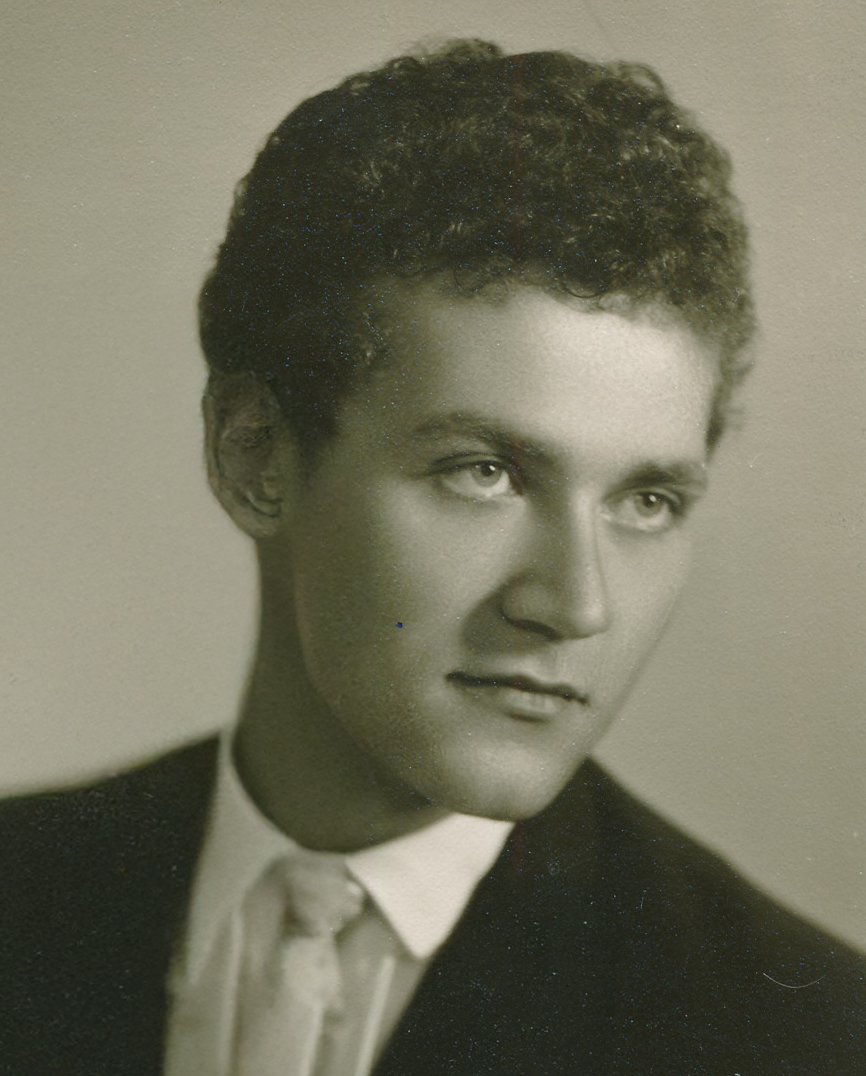

Josef Staněk was born on 19 March 1939 in Kateřinice near Vsetín. His mother, Štěpánka Staňková, was unmarried, and Josef was taken care of by his grandparents on a small farm from his early childhood. During the Second World War, partisans were very active in Wallachia; as a young boy, he witnessed a shooting during the arrest of one of them. He and the other boys also went to observe the training of young German soldiers in the nearby quarry. After the war, he and his grandparents went to settle in the border area in Staré Město pod Králickým Sněžníkem, where his grandfather was a horse driver, hauling wood to the sawmill. They did not stay there long, however, and soon returned to Kateřinice, where he joined a scout troop and was active in it even after the Junák was banned in 1950. At the age of thirteen, he moved to Hanušovice to live with his mother, who had married and finally taken her son in. In Hranice, he graduated from an industrial school specialising in woodworking and in 1958 went to the University of Forestry and Woodworking in Zvolen. He joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia during the war in 1964, and was later enlisted in the cadre reserves. He started his professional career at the North Moravian Timber Plants, quickly worked his way up and at the age of 28, became the director of the plant in Ostrava-Poruba. In the second half of the 1960s, he became a supporter of Ota Šik’s economic reforms, but his hopes were ended by the Soviet invasion of Ostrava on 21 August 1968. Although he disagreed with the entry of Warsaw Pact troops, he was vetted and sent to Prague in 1969 to join the Central Bohemian Timber Plants. Four years later, he joined the Czech Planning Commission, where he worked under Stanislav Rázle and remained in his position until November 1989. In retrospect, he assessed socialism as a good, but incorrectly implemented ideology. At the time of filming, he lived with his wife alternately in Prague and in Pekařov in the Šumperk region, where he carved wooden sculptures.