Deny me like Peter had denied Christ, or you’ll never get anywhere in this godforsaken system, my father had always advised me.

Download image

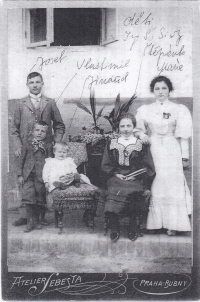

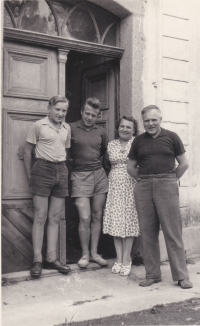

Jaroslav Sixta was born on the 28 March 1936 in Velim near Kolín. His parents farmed on an estate with about 36 hectares of fields, which had belonged to them since the 19th century. During World War 2 a part of the family was involved in the resistance movement. In 1942 they were meant to hide the parachutists from London that were meant to assassinate Reinhard Heydrich. The Sixta family had even built them a special hideout. However, his mother got scared at the last moment and refused to take on the risk. His cousin Miroslav Vojtěchovský, who had negotiated the hiding of the parachutists, was executed by the Nazis. After February 1948 the communists started to harass his family in relation to collectivisation. In 1951 they nationalized both his house and estate and he was forced to move to Kouřim. His father was sentenced to half a year in prison under the pretext of failing to supply the milk quota. The mother of three then moved to Nespek u Benešova. Jaroslav couldn’t study, being the son of a landlord, and so completed an apprenticeship in a sugar mill. He later studied at an electrotechnical industrial night school in Prague. He worked in, among others, the Uranium Mine Project Institute. In 1968 he emigrated along with his wife and three kids to Vienna. Afterwards he gained asylum in Canada. They settled down in Montreal, where he had family. He started to make a living there as a maintenance worker and later worked as oversight on construction sites. He got into a project agency and took part in the project Hibernia for mining oil in the Atlantic Ocean. He also functioned as a construction inspector on an airport construction site in Kenya. After the fall of the communist regime his family was returned their homestead in Velim as part of the restitutions. Jaroslav Sixta repaired the house and has started to return there. In 2021 he lived alternately in Montreal and Velim.