I completed the hunger march in my pram, my brother later gave Krnov a statue of the Madonna

Download image

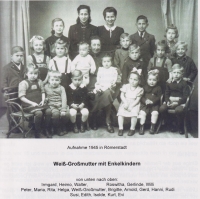

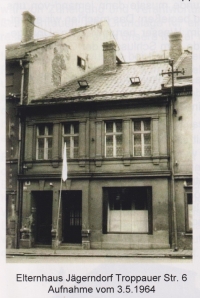

Helga Rügamer, née Titze, was born on 5 April 1944 in Krnov. In June of 1945, at one years old in her pram, she took part in the multiple-day Krnov hunger march, during which three thousand German inhabitants had to suddenly leave the town and around three hundred of them lost their lives. Helga Rügamer has no memory of this sad event herself, nor does she remember their several days stay at the Cvilín concentration camp. She does however know the progress of the march in detail from her mother and seven siblings, who walked tens of kilometres by her side. The one hundred and twenty kilometres long march ended in Králíky, from which the Germans were transported in cargo trains to the Krušné hory Mountains and expelled on foot via Cínovec. Helga’s father Rudolf Titze, a Krnov tanner, wasn’t allowed to do business in East Germany. Apart from the oldest sister, all the Titze siblings fled West, with Helga crossing over in Berlin on a bicycle in 1960. Since 1964, Helga Rügamer has regularly returned to the town of her birth, during the previous regime they held family meetings there. In the last few years she has taken part in symbolic reconciliatory events, just like her recently deceased brother Walter Titze. He even had a copy of the local Holy Mary statue made for the Krnov church, which is known worldwide as the Madonna of Dachau.