Most of my classmates were killed in the Soviet war

Download image

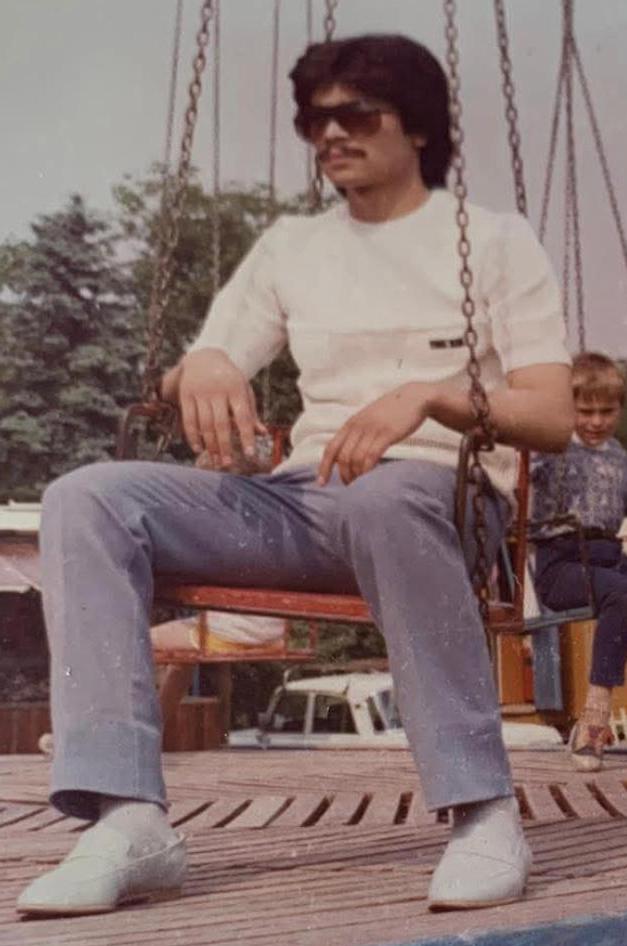

Fawad Nadri, an Afghan businessman living in the Czech Republic, was born in Kabul on July 10, 1968. He comes from a well-to-do middle-class family. His father was in the “carpet business”, but during the Soviet occupation after 1979 he joined the Communist Party and became the director of a state enterprise engaged in carpet export. The son graduated from high school in 1985. Unlike most of his classmates who were killed in the Soviet war, he managed to avoid being brutally recruited into the Soviet-controlled Afghan army and thus did not have to fight against the guerrilla mujahideen from among his own countrymen. He was admitted to a college of economics. As part of a government programme, he was then sent to study in Czechoslovakia, then a “friendly socialist country”, in September 1985. He attended a nine-month language course in Dobruška and from 1986 to 1992 studied at the Institute of Tropics and Subtropics at the University of Agriculture in Prague. In 1991, his parents and sister left Afghanistan and settled in Germany. Fawad stayed in Czechoslovakia, and after the Velvet Revolution began importing leather and textiles into the country, gradually adding other business activities. In 2005, during the coalition’s Operation Enduring Freedom, which also involved the Czech army, he founded the Czech-Afghan Joint Chamber of Commerce, which promoted trade and cooperation between the two countries. He headed a programme under which Afghan pilots and military technicians came to the Czech Republic and underwent training in Hradec Králové. The Czech-Afghan Joint Chamber of Commerce was later followed by the newly established Czech-Slovak-Afghan Chamber of Commerce. In connection with the activities of both chambers of commerce, he visited Afghanistan again, the last time in July 2021, just before its retaking by the Taliban. Fawad Nadri is a married father of two and lives in Prague.