The Communists needed to regulate everything

Download image

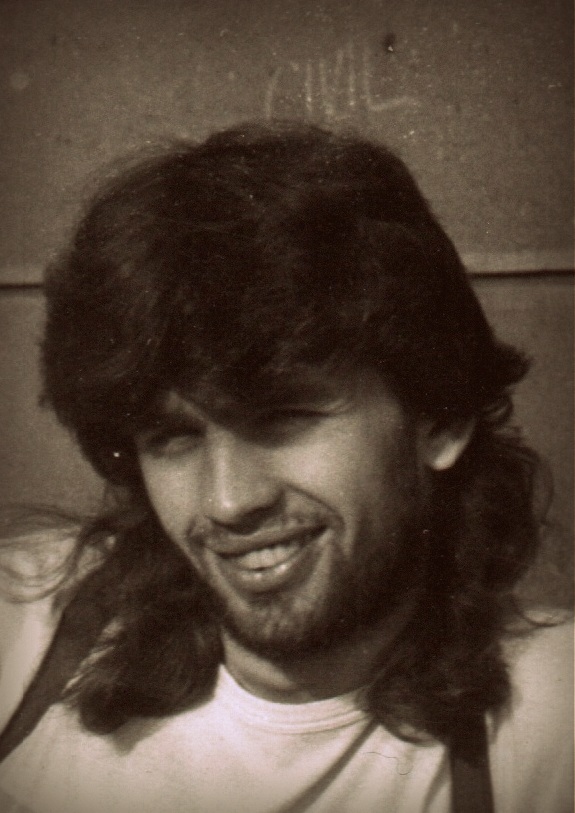

Leoš Motl was born on 31 December 1967 in Ústí nad Orlicí and spent his childhood in the nearby village of Knapovec. He was the only son of a local postman. He hardly knew his father, he died tragically when his son was five years old. After elementary school, he joined the grammar school in Ústí nad Orlicí, where he first met the then forbidden literature and music and made short contact with dissent. After graduation he went to Pilsen to study at the University of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering. He was intensively interested in all areas of culture, and enjoyed studying philosophy. He often organized events organized by students at the faculty and at the then Socialist Youth Union. On Friday, November 17, 1989, he attended a planned meeting of university students in Smetana Park in Pilsen. And that same evening he heard from foreign radio about events at a much larger demonstration in Prague. The following Monday, directly at the faculty, at the instigation of a witness, the students expressed a minute of silence to support their colleagues in Prague. During the following hectic days he became one of the main organizers of the student occupation strike and a member of the student strike committee in Pilsen. He was in charge of the printed stuff, looking for objective information, leaflet printing and distribution. Shortly after the Velvet Revolution, he was a member of the Academic Council and assisted in the founding of the University of West Bohemia. At the same time he graduated and in 1990 he started his business. He founded his own advertising studio, later returned to university and worked at Ladislav Sutnar’s Faculty of Design and Art. In 1999 he became one of the signatories of a statement by former student leaders entitled “Thank you for leaving!” and shortly thereafter, during one parliamentary term, he worked in local politics. He lives in Pilsen and still actively engages in civic matters.