Every day I am grateful to be living in an open society

Download image

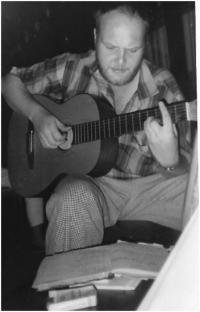

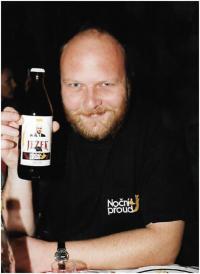

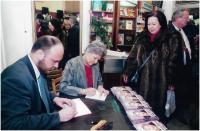

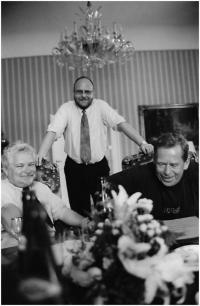

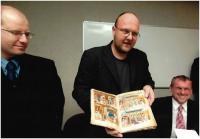

Vlastimil Ježek was born on 24 July 1963 into the family of a mechanic and hotel-school graduate in Prague-Karlín. After primary school, in 1978, he began attending a grammar school in Prague-Kobylisy, which he completed in 1982. He failed to enter the Veterinary University in Brno and was employed as a construction worker until 1983, after which he attended three semesters at the Faculty of Construction of the Czech Technical University in Prague. In 1983-1987 he worked as a carer for mentally retarded children while continuing his education. In 1984 he decided to study at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University; he passed the entrance exams and was accepted. In 1986-1987 he and other students organised a noticeboard newspaper, later the printed magazine Situace (The Situation); he held “flat” seminars and lectures at home, and in 1988 he and Zdeněk Tichý organised a twelve-part series of lectures on surrealism at the school. That same year they published a joint appeal against the banning of books. In November 1989 he was a major figure in the student strike movement. Upon earning his degree he worked as a journalist at the daily newspapers Lidová demokracie (People’s Democracy) and Práce (Work) in the years 1990-1993. In 1993 he succeeded in an open competition for the post of Managing Director of Czech Radio, and he retained this position until 1999. That same year he signed the civic appeal Děkujeme, odejděte! (Thank You, Now Leave!). In 1999-2004 he worked as the editor-in-chief of the magazine Naše rodina (Our Family), and in 2004 the minister of culture appointed him Managing Director of the National Library of the Czech Republic. Under his direction the library launched preparations for the construction of a new, modern building and organised an international architecture competition. However, the building plans ended up being scrapped, and Ježek was removed from office in 2008. In October of that year he was unsuccessful candidate for the Senate elections for the Christian Democratic Union - Czech People’s Party. Since 2012 he has been employed as the chairman of the board of the public limited company Obecní dům (Municipal House). He publishes in newspapers and magazines, he is the author and co-author of four books and history textbooks. He has three daughters from two marriages, he lives with his family in Prague.