Communists are bastards

Download image

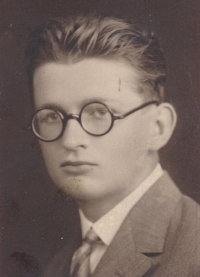

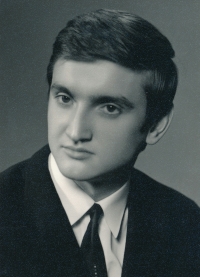

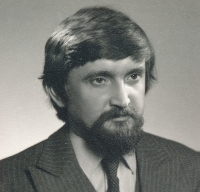

Tomáš Mikeska was born on 22 January 1948 in Javorník. His childhood was marked by the arrest of his father Antonín Mikeska in 1951. For alleged espionage for the Vatican, the director of the archbishop’s forests was sent to prison for nine years. This left his mother Antonie Mikesková alone with their three children. As a child he used to visit his father in Leopoldov or Valdice. With the support of her immediate family and the community of believers in Javorník, she managed to survive for seven and a half years before her husband was released. As soon as he returned home, she lost her job. His father was never able to return to his profession as a lawyer and worked in the blue-collar jobs until his retirement. The family moved to live with grandparents in Ostrava, because both parents found work at the Klement Gottwald New Steelworks, which, among other things, stood on the land of his grandfather Tomáš Mikeska without the owners’ knowledge. The believing family found themselves in a strongly secularized Ostrava. The fact that the son Tomáš attended a religious courses was to prevent him from being admitted to grammar school. Although the school refused such an assessment, he did not get into his dream secondary school and began to study at technical school in Přerov. In 1967, when he took the university entrance exam, his father’s fate no longer had any influence on his son’s career. He got into the University of Mining without any problems, where he chose a newly emerging field of study focused on the then novelty: computers. As a software engineer, he started working with the Ostrava Regional Hospital during his studies and after graduation he found his first job and wife there. Together with medical experts, he created a digital list of malignant neoplasms, which is still used today. In 1988 he moved to Prague with his family and together with his wife, also a computer scientist, started working at the Federal Statistical Office. Immediately, he also threw himself into the demonstrations that were appearing in the capital. He also joined the Národní Street events on 17 November 1989, although he did not aim for this rally. He founded Civic Forum in the Federal Statistical Office, and also plunged into municipal politics. As mayor of Prague 3, he led the district out of high debt and advocated the erection of a monument to Winston Churchill in front of the University of Economics. It was he who, under conspiratorial circumstances, married Czech President Václav Havel and his second wife Dagmar. In 2002, he resigned from his home Civil Democratic Party (ODS) party. He headed the association that led to the rescue of the Žižkov Freight Station. In 2025, Tomáš Mikeska worked on the supervisory board of the Museum of the Memory of the XXth Century and on the committee for territorial development in Prague 3, on the finance committee and on the energy dispatching in Prague 3.