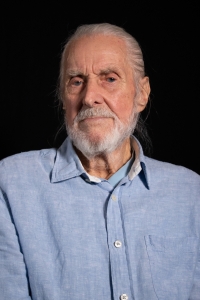

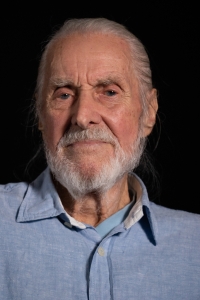

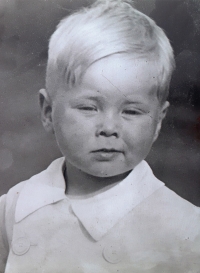

Francisco - child in war

Download image

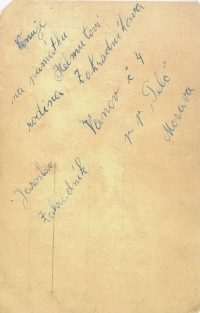

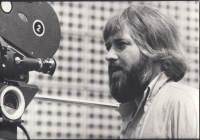

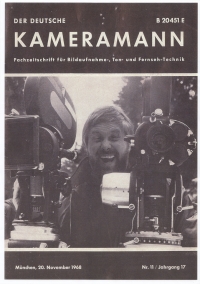

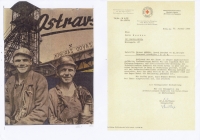

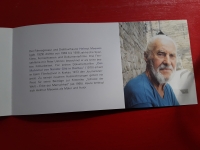

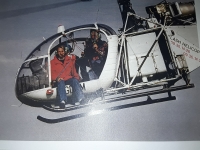

Helmut Meewes was a child soldier. In principle, he had little choice, and no one asked his parents. He was born on 15 November 1929 in Hamburg. In 1944, his Berlin school class was evacuated to Řevnice near Prague, from where he was later taken by the SS to a training centre in Pilsen. He was fifteen and a half years old when he took part in one of the last firefights of the Second World War in Wenceslas Square in Prague on 9 May 1945. He was then in a contingent of prisoners of war and underwent a gruelling march on foot to the Austrian border, a stay in a forest prisoner-of-war camp, a work assignment with peasants and several years of forced labour in the mines of Ostrava. All this as a minor. He was released to Germany at the end of 1948. A convinced pacifist and vegetarian, in the 1960s a fan of hippie culture, he eventually developed into a successful filmmaker and made, among other things, the art film The Dachau Monument by Nándor Glid. From childhood to the present day, he has also painted pictures. He signs them under his non-German-sounding name - Francisco.