I began to hate the Bolsheviks in the military

Download image

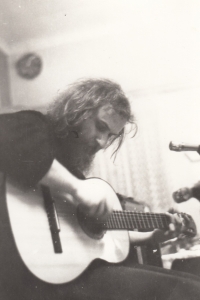

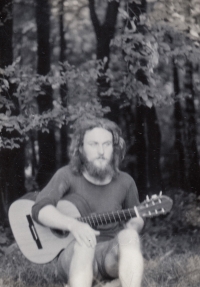

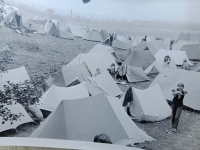

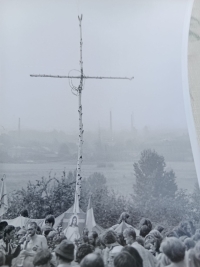

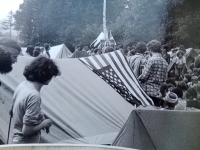

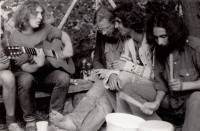

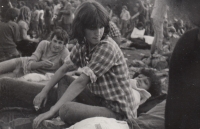

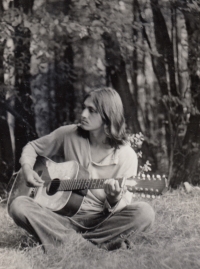

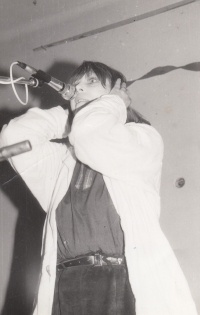

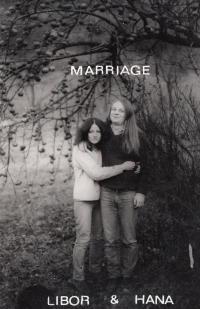

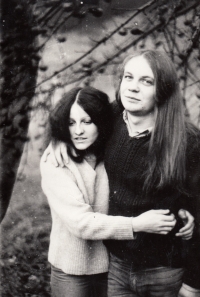

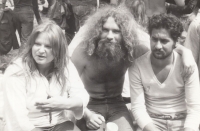

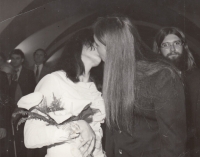

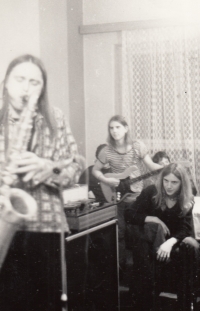

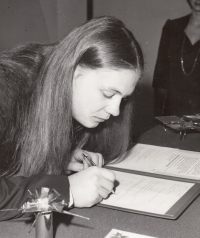

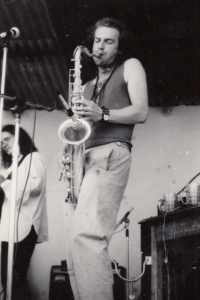

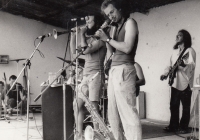

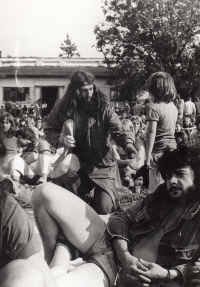

Libor Malý was born on September 19, 1962, in Slavičín. His athletic parents, Marie and Josef, devoted themselves to him from an early age and taught him to skate, ski, and ride a bike. At the age of thirteen, however, Libor began to devote himself to rock music instead of sports. Together with his older friends, the so-called “máničkas,” he went to concerts—the highlight of which was a visit to the relatively free Budapest, but also to the pilgrimage site in Częstochowa, Poland, where a hippie commune lived at the time. Because of this, he underwent his first interrogation by State Security at the age of seventeen. Due to his connections with the underground and his involvement in the creation and distribution of samizdat, he received a poor assessment and was forced to enlist in a penal military unit in Kramolín in 1983, where he participated in the construction of the Dukovany power plant. He remembers his military service as a terrible period full of injustice and poor living conditions. After his release from the barracks, he and his wife Hana became involved in the Moravian samizdat movement again, acting as a liaison between the then Gottwaldov, Vsetín, and Rožnov pod Radhoštem. In 1988, he signed a petition against the entry of Warsaw Pact troops into Czechoslovakia on behalf of himself and his wife, for which he was interrogated again. In November 1989, he took part in the Festival of Czechoslovak Independent Culture in Wrocław, where exiles Jaroslav Hutka, Vlastimil Třešňák, and Karel Kryl performed on one stage. After the Velvet Revolution broke out, he went to Prague, where he took part in demonstrations and witnessed Václav Malý’s speech at Letná on November 25, 1989. In times of freedom, he fulfilled his dreams by traveling around the world and devoting himself to his lifelong hobby – cycling. In 2025, he is deeply affected by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, where he has friends and where he regularly travels and witnesses the horrors of war. At the time of filming the interview, he was living in Vsetín.