I am grateful for the opportunity to experience it and to have such people around me

Download image

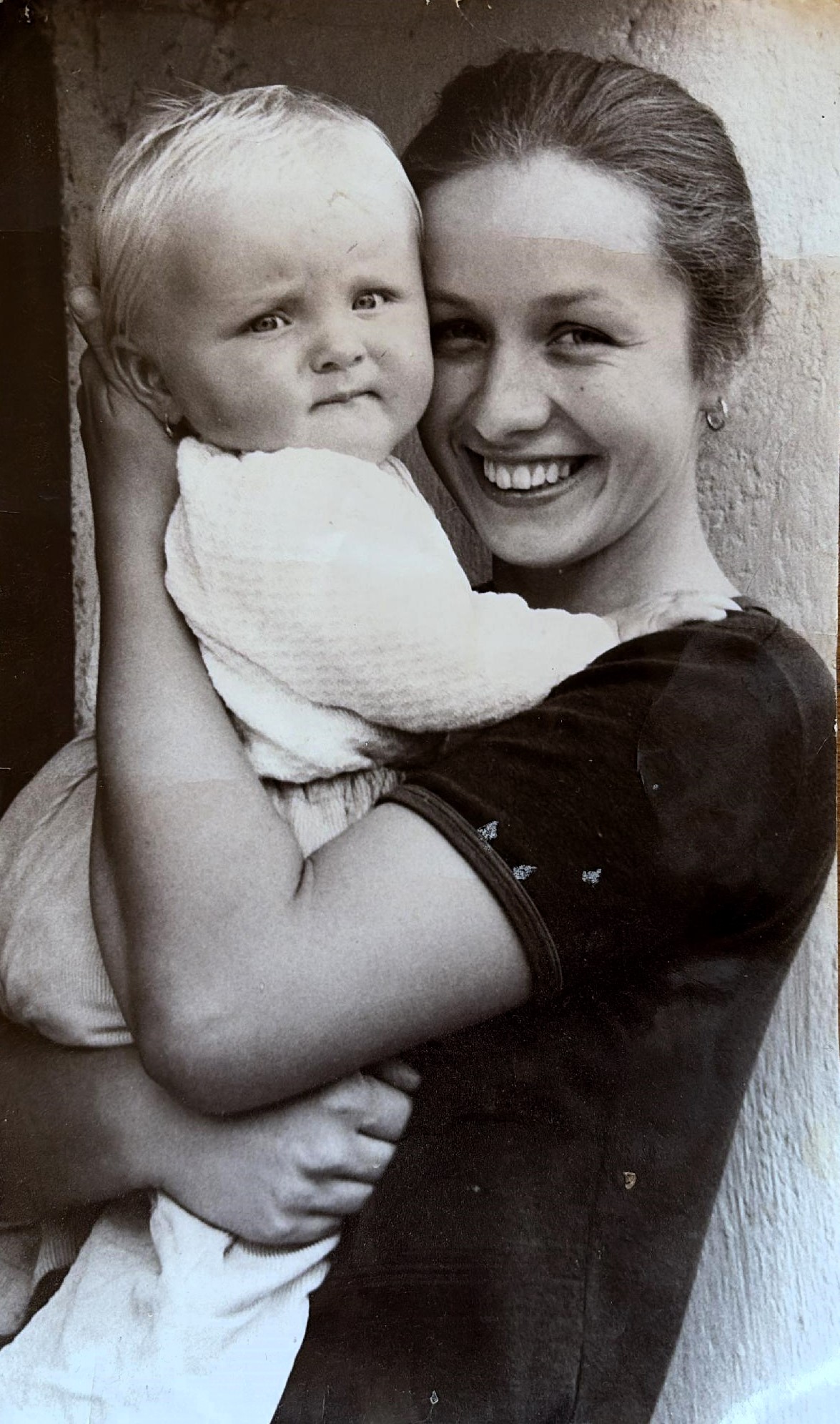

Lenka Makovcová Demartini was born on 30 April 1964 in Prague, into a family with a long and famous tradition - producers and exclusive suppliers of soaps and perfumes for the imperial court. After finishing primary school, she entered grammar school in Strašnice, where she showed her attitude towards the communist regime by permanent rebelliousness. After her graduation exam, she worked briefly in the broadcasting department of Czechoslovak Television and then continued her English and Czech studies at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University. In 1985, after a conversation with English-speaking tourists, she was subjected to interrogation in Bartolomějská Street, during which State Security threatened her with an unconditional sentence and with taking her child away for allegedly subverting the republic and defaming a socialist leader. In the mid-1980s, Lenka Demartini became part of the opposition community around Petr Placák. In 1988 she joined the independent initiative Czech Children, with which she participated in spreading of samizdat and independent activities. In January 1989, she was a direct participant in the demonstrations during Palach Week. After the Velvet Revolution, she took up English and American Studies at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University and later theology at the Catholic Theological Faculty of Charles University, where she successfully passed the state doctoral exam in 2022. In the same year, she received a Certificate of Participation in Resistance and Resistance against Communism from the Minister of Defence. In 2025 she lived and worked in Prague.