As a relative of Antonín Dvořák I keep returning to Bohemia to play the organ even after the expulsion

Download image

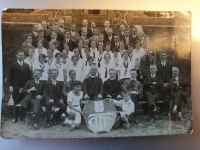

Rosemarie Kraus, maiden name Dvořák, was born on 12 November 1941 in Chlumec near Ústí nad Labem, previously called Kulm in German. She was from a musical family, her great grandfather František Dvořák, brother of the famous composer Antonín, married a German, who then returned to her home region of Ústí nad Labem after his early death. Her grandfather and the composer’s nephew, also named František and who still spoke Czech, lead an orchestra in Chlumec, and her uncle played the organ. However the family otherwise spoke in German, in the Chlumec dialect. Her father Josef was conscripted in 1943 and never returned from the war. He fell into American captivity and later settled down in Bavaria. Rosemarie’s family was at first dispossessed in May of 1945, and then in August 1947 they were deported to the Soviet zone of Germany, with an eight-day stay without food and water at the camp in Všebořice near Ústí nad Labem. Their grandfather who was able to avoid expulsion (not however, dispossession) decided to stay with the family. Rosemarie’s childhood memories of these events are dominated by images of the toys (her doll, a wooden angel), which she brought from home as well as the permanent consequence of her deformed feet which were unable to properly grow as she only had one pair of tight shoes. After several months living in the Soviet zone their mother succeeded in getting permission to leave for West Germany to be reunited with her father, the grandparents were only allowed to follow in 1949. Rosemarie studied the organ in Bavaria at the Sisters of the Cross in Werneck, originally from a monastery in Cheb. After her mother’s death she decided not to continue her university studies, instead she looked after her grandfather until his death in 1965, working as a tax advisor. In the 80s she helped spread a petition for the release of Václav Havel from prison throughout Germany, initiated by the International Society for Human Rights. To this day she still plays in churches, since 1984 she has been visiting and playing in Czech churches. She is worried about the state of pipe organs in the country. Each year she participates in a pilgrimage in her hometown of Chlumec, as well as making an effort to support the renovation of the organ in nearby Bohosudov.