I regarded the State Security’s surveillance as the price I paid for my alternative way of life.

Download image

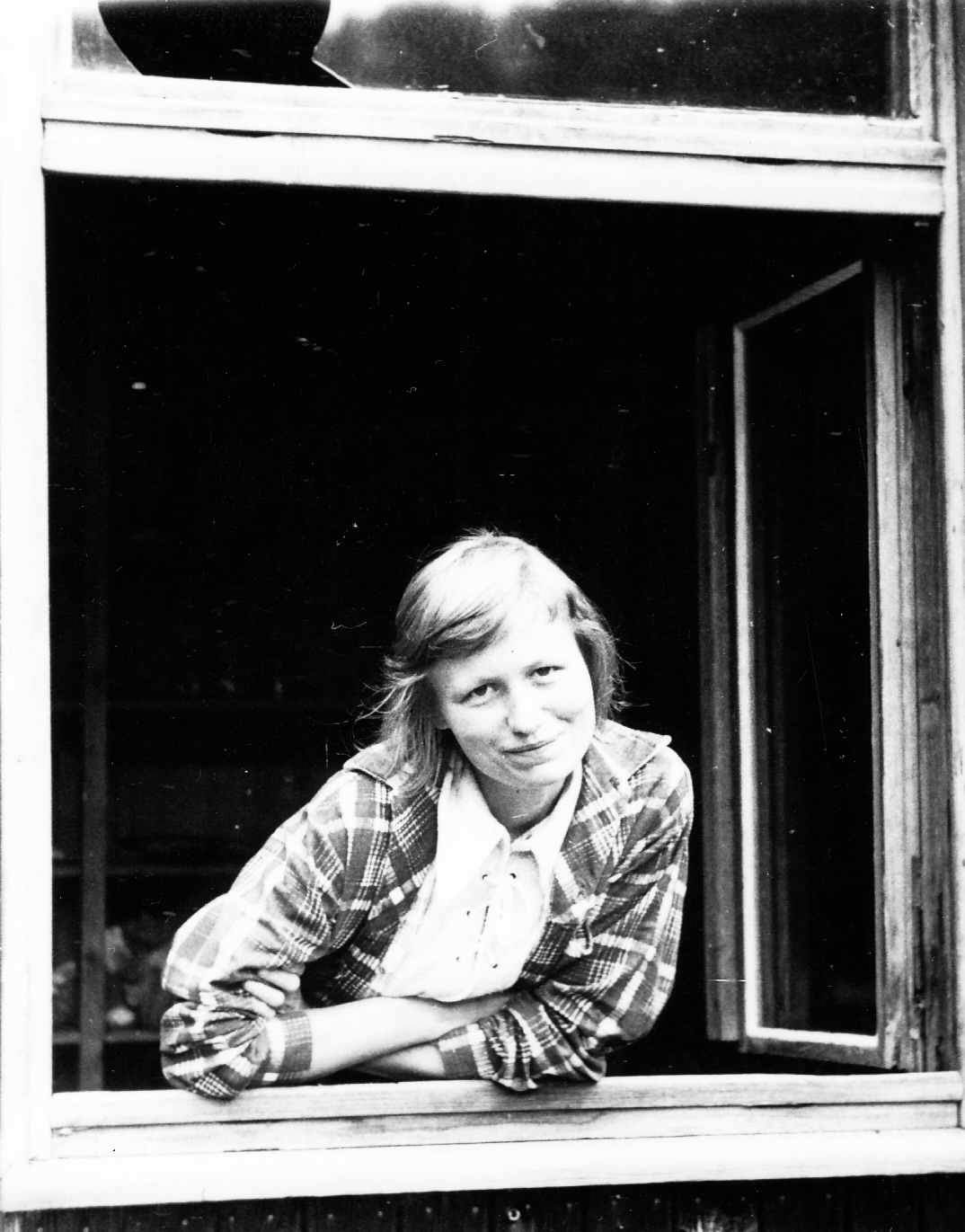

Jana Kašparová, née Ryšavá, was born on October 24, 1948, in Miroslav in the Znojmo region. Her family was marked by wartime events when, during the bombing of Miroslav at the end of World War II, her uncle and cousin were killed. The family was also affected by collectivization, during which the gardening business owned by her grandfather was nationalized and her father was forced to join an agricultural cooperative (JZD). In her youth, Jana Kašparová was shaped by the environment of the Evangelical congregation in Miroslav, which created an alternative space not only for spiritual life but also for education. During her adolescence, she repeatedly took part in so-called summer youth camps, where she worked during the day in forestry in the border regions and spent the evenings studying and socializing, including with East Germans. She studied theology at the Comenius Evangelical Faculty of Theology in Prague, where she experienced both the more liberal atmosphere of the Prague Spring and the subsequent tightening of conditions during the period of normalization. She witnessed the occupation by Warsaw Pact troops in August 1968 from West Berlin, where she happened to be staying at the time. In 1971, she became involved in a leaflet campaign calling for a boycott of the Communist Party. After completing her studies, she obtained state approval and took up a position as a vicar in Opatov in the Jihlava region. However, she was under constant supervision by the church secretary and later also by the State Security (StB), due to her acquaintances—including Jan Litomiský—and her numerous contacts abroad. The StB regularly summoned her for interrogations. She did not sign Charter 77 but helped distribute it. She was denied state approval to serve as a pastor in Vanovice na Hané and instead worked there as a parish assistant; her activities were once again monitored by the State Security. After 1989, she helped establish the Evangelical Academy in Brno, which is still active today. In 2025, Jana Kašparová was living in Bílovice nad Svitavou.