One must not be afraid

Download image

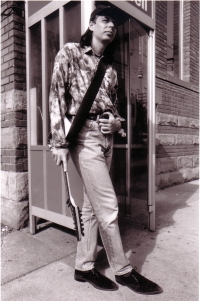

Josef “Joe” Karafiát was born on February 16, 1957 in Vinohrady, Prague, and spent his school years in Prague 6. In 1968, he witnessed the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops. During his apprenticeship, he began to devote himself to music. At the age of twenty, he and his friends decided to emigrate via Frankfurt to London. He spent two years in England, learning English, earning money by playing the streets in the tube and teaching guitar. He then travelled to Canada, where he lived first in Ottawa and later in Toronto, where he also devoted himself to music. In the 1990s, Josef returned to Czechoslovakia due to his sick mother. In 1992 he started playing with the band Garáž, from 1997 he became a member of the renewed band The Plastic People of the Universe and later he also performed in the solo project of Milan Hlavsa Šílenství. At that time, he also met Václav Havel. He toured the world with the bands he was a member of, his home is still the Czech Republic.