I feel like German but I behave like a man

Download image

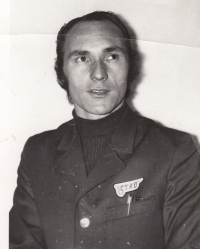

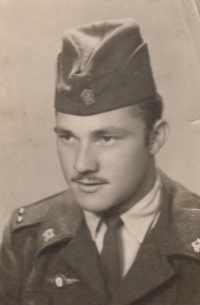

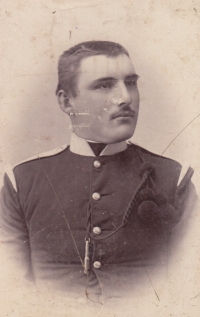

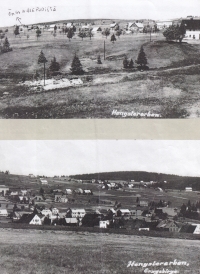

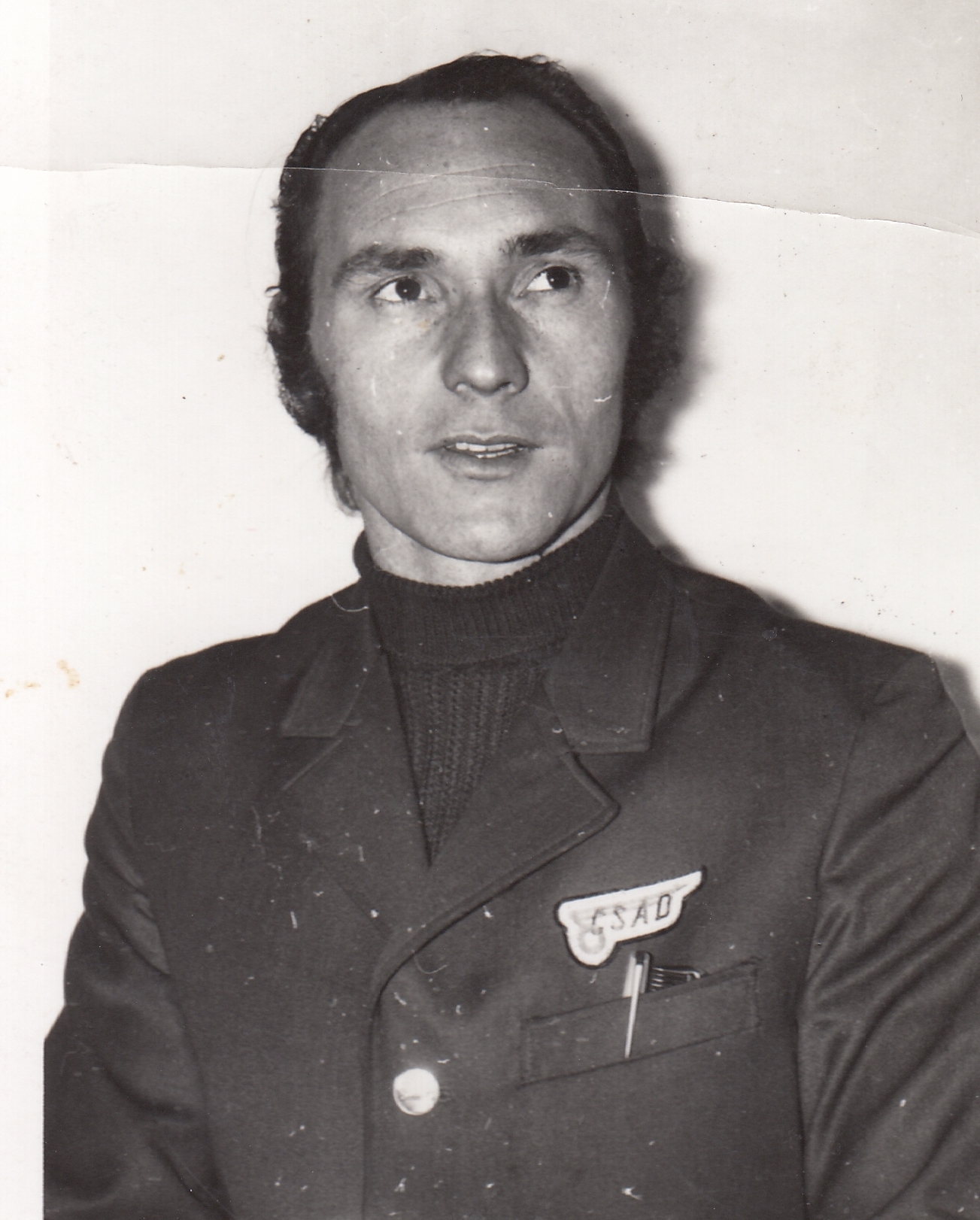

Albert Iser was born on 5 April 1946 into a family of Erzgebirge Germans in the village of Hřebečná. His father Josef Iser worked as a miner in the local mines, his mother Marie, née Kraus, was employed in a glove manufactory. His father enlisted in the Wehrmacht during the war and served in Norway. After the war, the family spent three months in an internment camp, but were not deported because of their father’s profession. The uranium mines in the Jáchymov region were in dire need of skilled labour. In the meantime, however, the Isers’ house in Hřebečná was occupied by settlers and the family was moved to nearby Abertamy. Only German was spoken at home, and after starting school Albert had problems because he did not speak Czech. After finishing primary school he trained as a glove maker. During his basic military service (1965–1967) he got his bus driving license and worked as a driver for the ČSAD in Jáchymov for the next twenty-five years. After the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops in August 1968, he drove a bus covered with anti-occupation signs for a month. As a German, he was not allowed to drive the bus on trips to the GDR. During the period of normalisation, he applied for emigration six times, but due to official delays he never got all the necessary documents. In the 1990s, he took a job as a locksmith in the Jáchymov mines, where radon water was pumped for spa purposes at the time. In 2014, he underwent successful surgery for a brain tumor. As a flag bearer, he participated in mining festivals across the country.