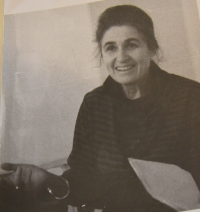

After returning from Terezín, I looked worried. By October, I was a normal girl

Download image

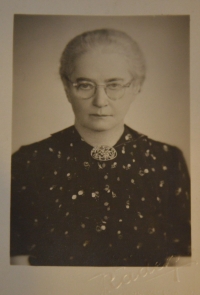

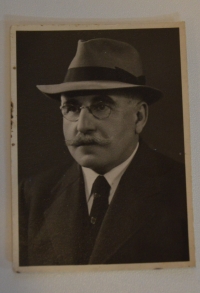

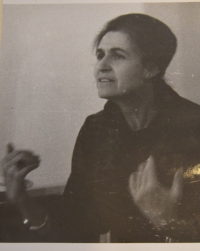

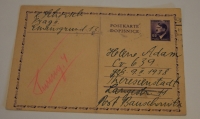

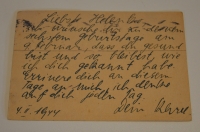

Helena Glancová, née Adamová, was born on February 9, 1938 in Prague to Julia Adamová, née Schorschová, and Gustav Adam. Her mother was of Jewish origin, her father was not. The couple divorced after a year. From 1943, she and her mother were interned in the Terezín ghetto, where they both lived to see the liberation. Most of her relatives perished in the concentration camps. In May 1945 they returned to Prague. Helena Glancová began to attend primary school, then secondary school. She graduated from DAMU, majoring in theatre directing. In her final year she completed an internship in Leningrad. After school she got a job at the East Bohemian Theatre in Pardubice. From 1964 she assisted Otomar Krejčí at the National Theatre. In 1965 she participated in the founding of the Prague Theatre behind the Gate. The theatre was closed down by the communist authorities in 1972. Helena Glancová then worked at Lyra Pragensis, which was part of Supraphon, until the Velvet Revolution. In 2025 she lived in Prague.