My father used to call me Spatz

Download image

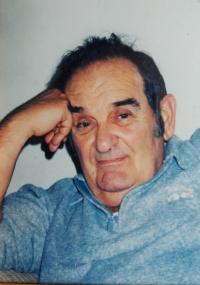

Annelore Finková, née Miszich, was born on 19 July 1940 in the city of Lyck in the former Eastern Prussia (nowadays the Polish city of Elk). Both of her parents were Germans, with her father working as a financial clerk and mother as an accountant. Annelore had an older brother. By the end of 1939, her father was drafted to the Wehrmacht and fell probably in 1945 in Poland. At the end of the war when the territory was divided between the Soviet Union and Poland, the family had to leave their home. After more than three weeks, they found accommodation in the village of Scharzenberg on the German side of Erzgebirge. A year later, they moved to their relatives’ house in Erfurt. Annelore Finková graduated from a medical school and worked in the field. She got married, divorcing seven years later. Her second husband Harry Fink had Czechoslovak roots and she moved there with two children to reunite with him in 1973. Due to his Jewish origin, Harry Fink spent a year in the Terezín ghetto, surviving the Auschwitz extermination camp where he was in a group dubbed the ‘Birkenau Boys’. He lost most of his family in the holocaust. The Fink family lived in Horní Slavkov, Ostrov and in Karlovy Vary. Annelore worked in Karlovy Vary as a spa medician and later as a nurse in Munich. She is retired and lives in Karlovy Vary.