My mom was lying motionless on the floor, next to her was my Dad’s coat covered in blood

Download image

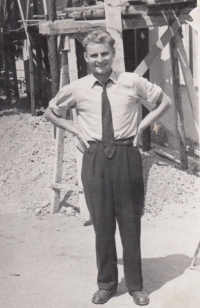

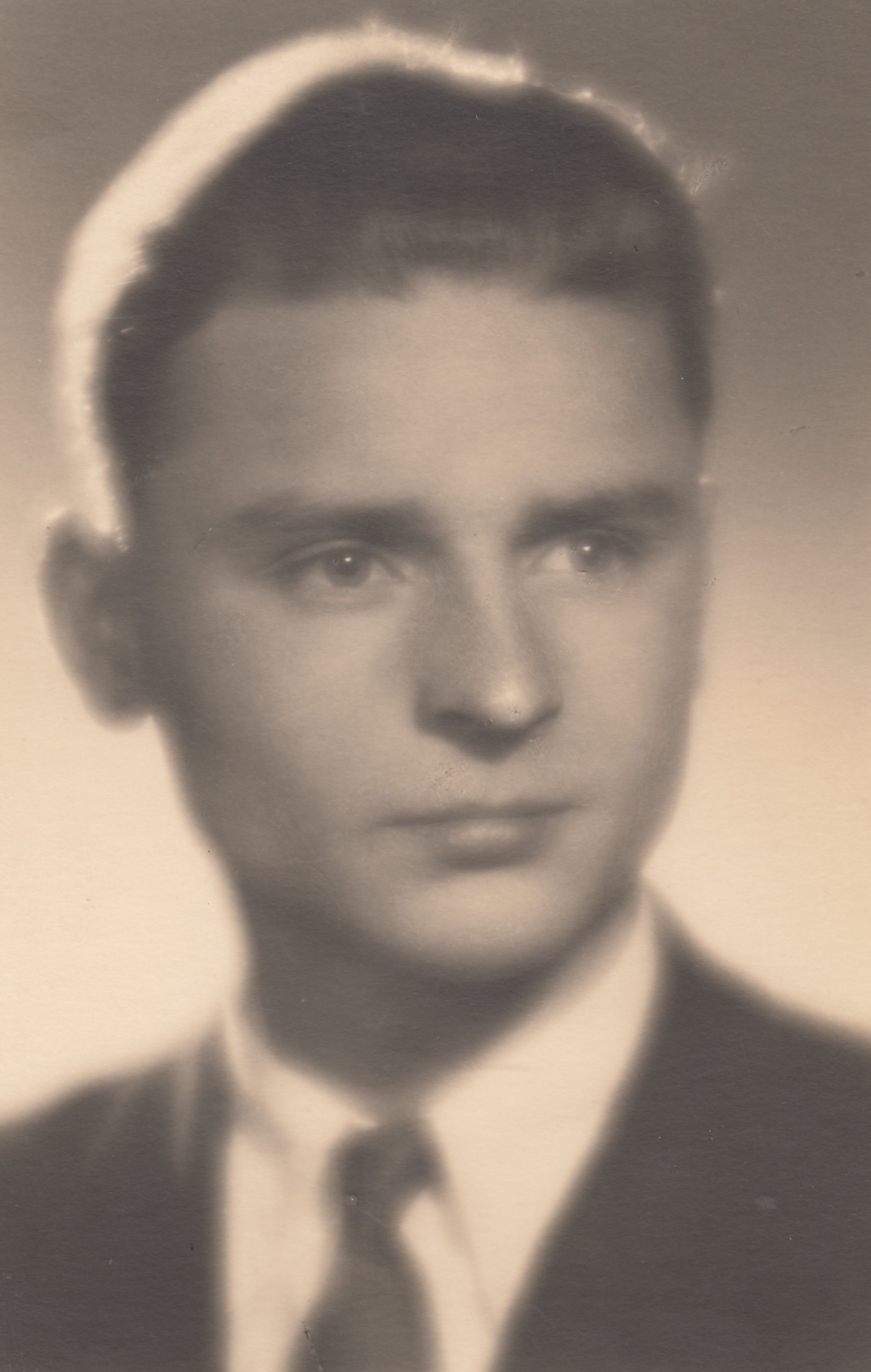

Josef Dvořák was born on September 18, 1927 in Lysá nad Labem. He spent his childhood in Čelákovice, where his brother Vladimír and sister Věra were born. In the summer of 1938, he was sent to a sanatorium in Dubrovnik, in what was then Yugoslavia, which is where he was when the Munich Agreement was signed. In 1942, he started attending a secondary technical school in Prague. After the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, his family’s house was searched. In 1944, he collected ammunition for partisans. His father was injured during an air raid by allied troops in the winter of 1945. Later on, Josef was sent to dig trenches for the German army, from where he managed excape an run back home. After the war, he joined Junák (a Czech organization of Scouts and Guides). In 1946, he graduated from high school and started working at the State Glass Research Institute in Hradec Králové. In 1949, he started his compulsory military service in Šumava, from where many soldiers fled across the border. He married in 1955, and he and his wife Milada had three daughters. In 1968, he signed the Two Thousand Words manifesto. In 1970, he was expelled from the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ). He led children’s sports clubs in Hradec Králové. He enjoyed boating and orienteering, visiting castles and fortresses, and singing in the church choir. In 2022, he lived in Hradec Králové.