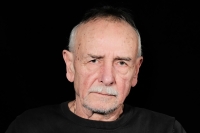

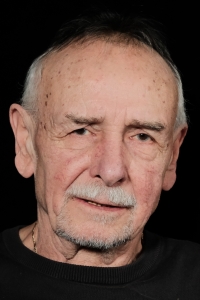

Signing to a mine was the only way to escape cooperative farmers

Download image

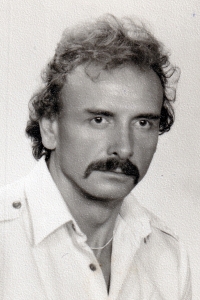

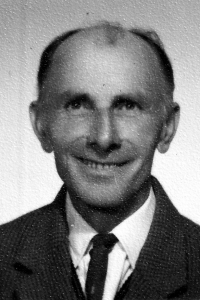

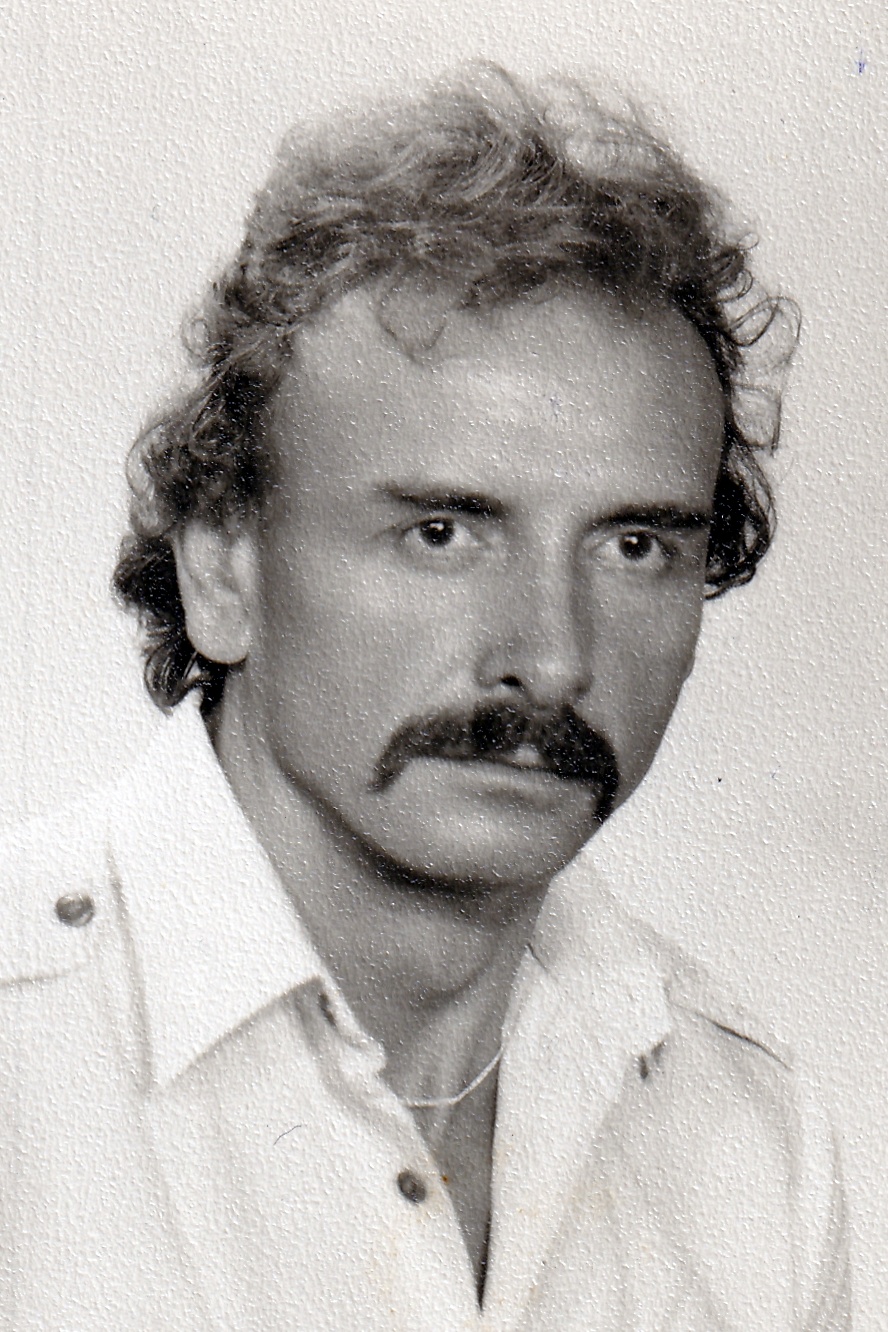

Ladislav Dosedla was born on 25 December 1947 in Znojmo as the second of eight children of Anna and Jan Dosedla. He grew up nearby, in Sedlešovice. His parents bought a farm there and farmed independently. Around 1953, they were forced to join a cooperative farm (JZD). His father spent three months in prison for beating a communist official. Ladislav Dosedla refused to be apprenticed at the cooperative, which was interested in him. He preferred to sign a contract with a coal mine in Ostrava. After graduating from the mining apprenticeship, he joined the Red October Mine in Ostrava-Heřmanice. When he was about 25 years old, his father committed suicide. The witness worked at Ostrava-Karviná Mines for 26 years. At the end of the 1970s, he started working as a shift foreman and then as the chief foreman of the extracting team. After reaching the maximum of the so-called dusty exposure and being transfered to the surface, he earned a living as a masseur. In 2023 he was living in Bruntál.