My parents lived with the knowledge that they had not surrendered to the regime, but at what cost

Download image

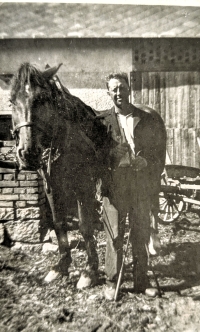

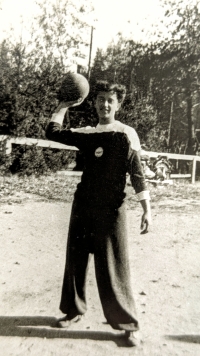

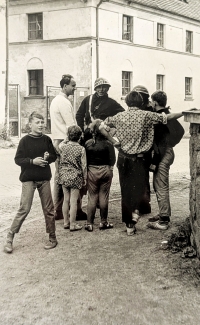

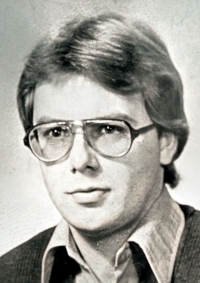

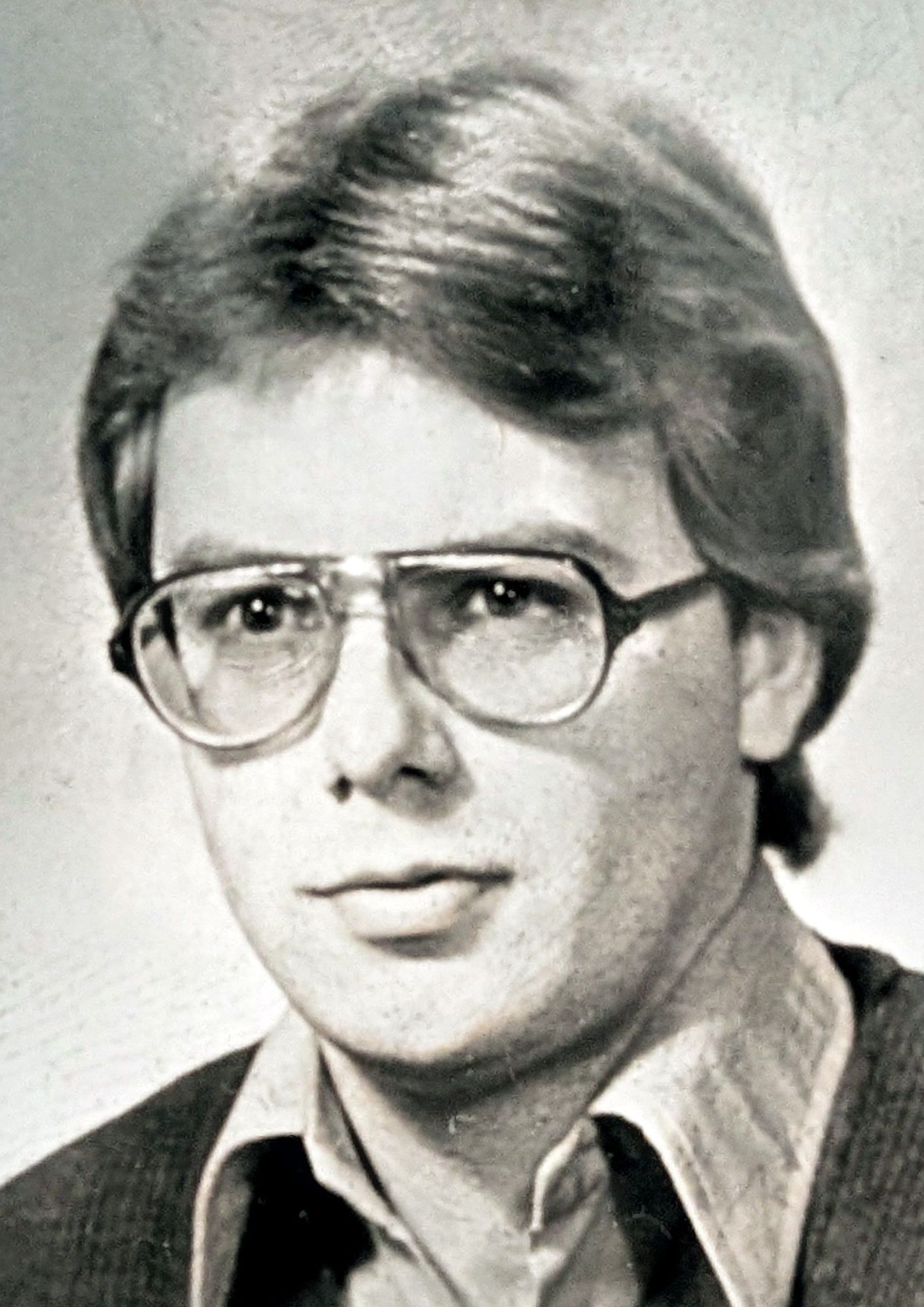

Petr Bruner was born on March 21, 1960 in Most to Jarmila, née Tichá, and Pavel Bruner. He spent his early childhood alternately with his grandparents in Kolinec and Volyně. His paternal grandparents had a relatively large farm with forests and fields, they also owned a tavern, a butcher shop and a carriage shop. The Communists took away a large part of their property after 1948. His family was religious, and he attended religious classes and ministered in the local church. He lived through the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops in Kolinec as an eight-year-old. At the beginning of normalisation he began to have problems because of his faith and was eventually not accepted to any secondary school. It was only thanks to the intercession of a certain regional secretary that he was able to enter an apprenticeship at the Škoda factory in Plzeň. Eventually, he was able to continue his studies and after graduation he was even accepted to study engineering - but he dropped out after three semesters. He served his basic military service as a tank commander in Jihlava. During the Velvet Revolution he participated in demonstrations in Pilsen. After the fall of the regime, he worked in Germany for over twenty years. In 2025 he lived in his grandparents’ house in Kolinec.