Becoming a miner was not his choice. The Communists decided the future of the son of a rebellious farmer

Download image

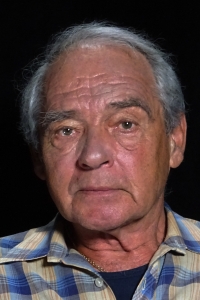

Jan Blizňák was born on 5 August 1943 into an evangelical family in Ratiboř, Vsetín region. His parents had a small farm, his father also worked in the forest, and his mother worked as a road controller. In the early 1950s they both lost their jobs and the family of seven, which included an invalid grandfather, was supported only by the farm with two hectares of fields. When the Unified Agricultural Cooperative (JZD) was founded in Ratiboř, the father refused to join it, and eventually stopped fulfilling the obligatory deliveries set up so that they would have nothing left. The Cooperative then forcibly took over their fields. The children were not allowed to go to secondary school. Jan Blizňák had to enter a mining apprenticeship in Ostrava. Even as a fifteen-year-old apprentice, he worked in the low seams of the Eduard Urx mine in Ostrava-Petřkovice. He spent almost 40 years at Ostrava-Karviná Mines, of which almost 20 years underground. After doctors diagnosed him with vasoneurosis and dusty lungs, he worked on the surface and then as a recruiter at the Staříč Mine. He was a long-time marker of hiking trails in the Beskydy Mountains and a nature guard. In retirement he earned extra money as a projectionist in the cinema Vlast in Frýdek-Místek. He created dozens of models of wooden churches, chapels and bell towers. In 2021 he lived in Frýdek-Místek.