I said it’s not fraternal aid. So I worked at the railway

Download image

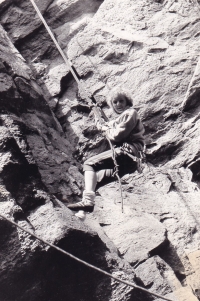

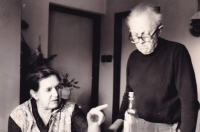

Eva Bělková was born on 7 February 1936 in Přerov to parents Hedviga and Bedřich Gazda. Her father, a lawyer, worked as a judge in Přerov before the war and later in Šilperk (today Štíty) in the Šumperk region. After the Munich crisis, the family had to leave the Sudeten town of Šilperk and the Gazdas moved to Velký Meziříčí, where they survived the war years. In the post-war period, her father Bedřich worked at the Extraordinary People’s Court in Znojmo, and in the 1950s he was involved in political trials as a judge. After primary school, Eva trained as a basket-maker in Morkovice in the Kroměříž region, and then worked in the local Zadrev company. She continued her education at the secondary school for workers in Brno and from 1957 to 1961 at the Pedagogical University in Prague (now the Pedagogical Faculty of Charles University). Before entering the university, she married Antonín Bělka and together they raised their son Martin and daughter Barbora. As a graduate of the pedagogical school Eva taught at primary schools in Ivanovice na Hané and Prostějov. During the times of the temporary liberation in 1968 she joined the Communist Party (KSČ) and at the Ivanovice nine-year school she also served as the chairwoman of the KSČ basic organization (ZO). As chairwoman of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, she publicly condemned the August invasion by Warsaw Pact troops. This was followed by expulsion from the party and professional persecution. It was only after the Velvet Revolution that she was able to return to the teaching profession, until then she worked for the Czechoslovak State Railways (ČSD). In 2022 Eva Bělková lived in Nezamyslice in the Prostějov region.