I was happy when the communist regime fell. In the 1990s, I felt disillusioned

Download image

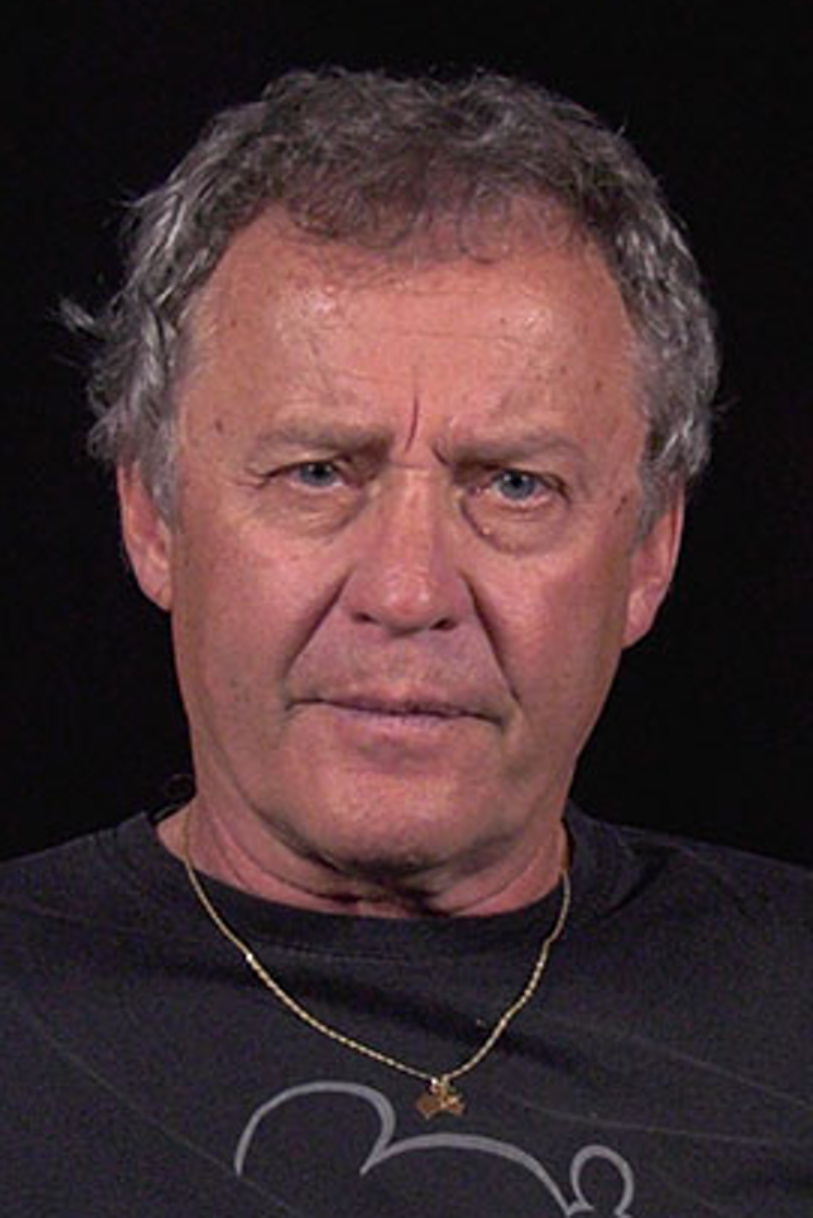

Zdenek Zukal was born on the 23rd of September 1954 in Olomouc. His mother worked as a shop assistant, his father was a radio operator for the Czechoslovak Navy. He graduated from the Secondary School for Film in Čimelice. He studied cultural theory at the Faculty of Arts at the Palacký University in Olomouc and later worked for the audio-visual centre of the university. In November and December 1989, he joined the anti-communist protests. He recorded dozens of hours of video footage of strikes, demonstrations, and of students and actors on strike visiting factories and villages in the region. Thanks to his video-journalism he spread the news of events linked to the revolution. In 1993, he founded his own television studio and started supplying private television channels with news coverage from his region. Charges were held against him for falsely accusing police officers in connection to a series of news reports he had made on the so-called Olomouc Affair. He was not convicted.