Be glad, that we have freedom

Download image

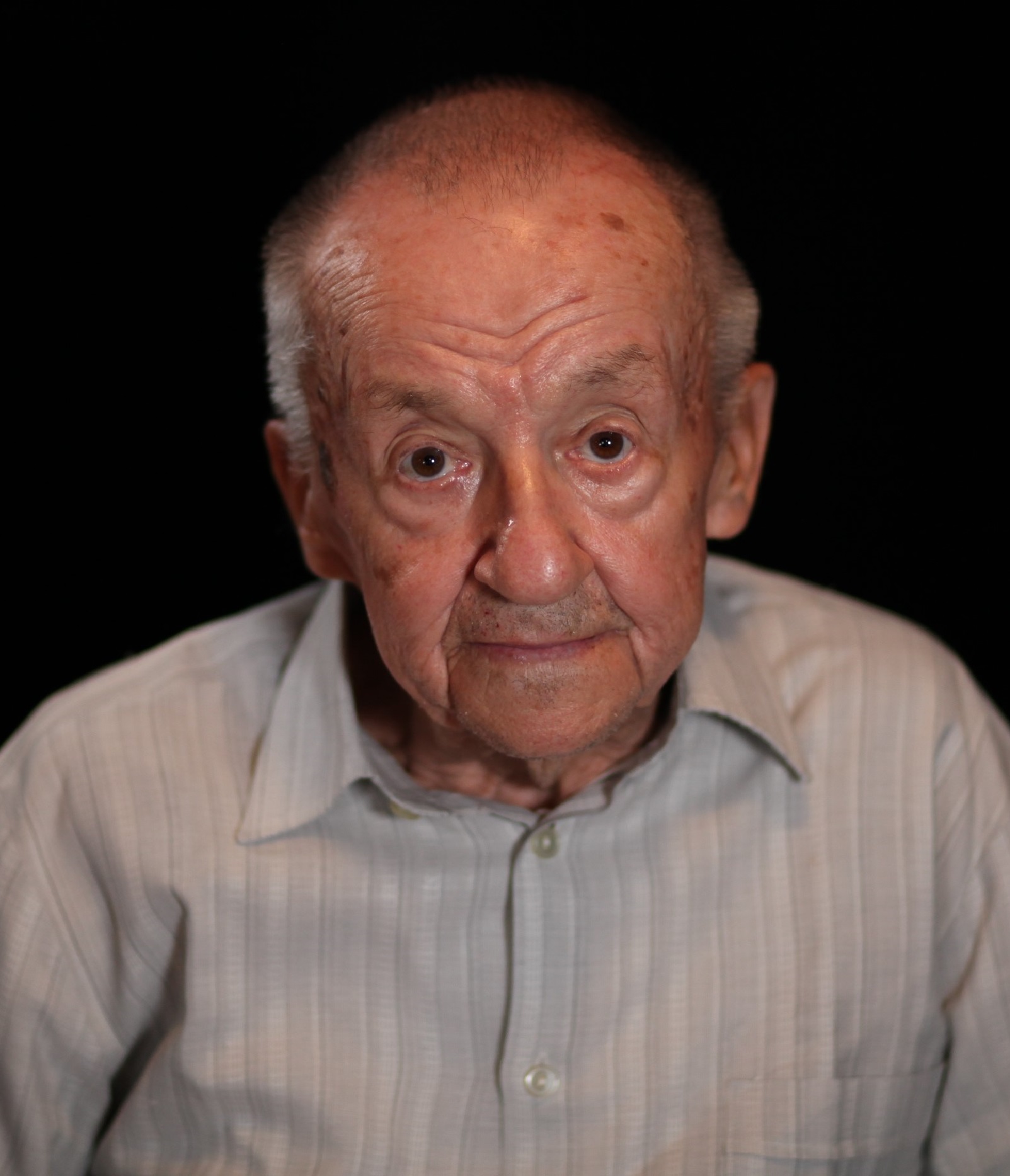

Josef Žanta was born on March 18, 1932 in Rožnov pod Radhoštěm into the family of the first republican lawyer Josef Žanta. He grew up in a functionalist villa built by famous architects, Mrs. Šlapeta’s siblings. During the Second World War, his father Josef Žanta took part in the anti-Nazi resistance, made a partisan link and passed on information from Vsetín’s Zbrojovka about the local production of weapons. Josef Žanta’s mother, although she was of Austrian origin, she was an enthusiastic Sokol member and patriot. Josef Žanta himself watched the execution of partisans as a child. His family had long-standing problems with the communist regime, whether it was the closure of his father’s law firm or the difficulty of the witness’s admission to university. During his basic military service, he took part in a combat alarm, when he and other soldiers arrested a saboteur. During the August occupation of 1968, Josef Žanta took part in protests and strikes in Tesla Rožnov. In 1987, he signed Charter 77, took part in a silent Catholic protest organized by the activist Augustin Navrátil, and in anti-regime demonstrations in Prague in January 1989, known as Palach’s Week. He faced interrogation of the State Security several times. The witness’s son Aleš also took part in anti-regime activities before 1989.