The future of Czech Scouting is in its past.

Download image

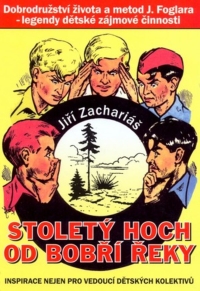

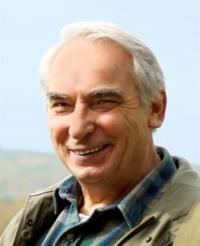

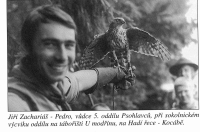

Jiří Zachariáš, nicknamed Pedro by Scouts, was born in Prague on April, the 16th, 1943 into the family of a bookbinder. He was strongly influenced by the atmosphere of his native district of Žižkov. In 1947 he joined the Scout troop lead by Zdeněk Bláha (a hero of the Prague Revolt). In the early Fifties, he joined Jaroslav Foglar’s troop, which functioned under the heading of the camping troop Dynamo Radlice. He remained there until reaching the age of a Rover. Starting in 1962, he and Jiří Kavka led the Hiking Troop within the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. In 1965 he took part in the founding of the Psohlavci [Dogheads, also the title of a classic Czech 19th century book - transl.] group, which had the general revival of Scouting as its covert goal. In 1968 he founded his own group, Spirála [The Spiral]. After Junák [the Czech Scout Movement] was dissolved in 1970, he took his troop into the youth camping union within the Sports Union Slavie Žižkov. He begun publishing the samizdat [illegal] magazine for Rovers, Cesta [Road]. Together with three adult Scouts he managed to take part in the 1975 world Scout Jamboree in Lillehammer. He was a signatory of Charter 77. In 1982 he rejoined Jaroslav Foglar’s troop, where he functioned as a leader until the early Nineties. In the post-November era, he took part in the founding of the Association of Scouts and Guides of the Czech Republic, a branch of the Junák organisation. He wrote several books and articles concerning the history of Scouting and Jaroslav Foglar, “Goshawk”.