We had to move out wearing only the clothes we had on at that moment

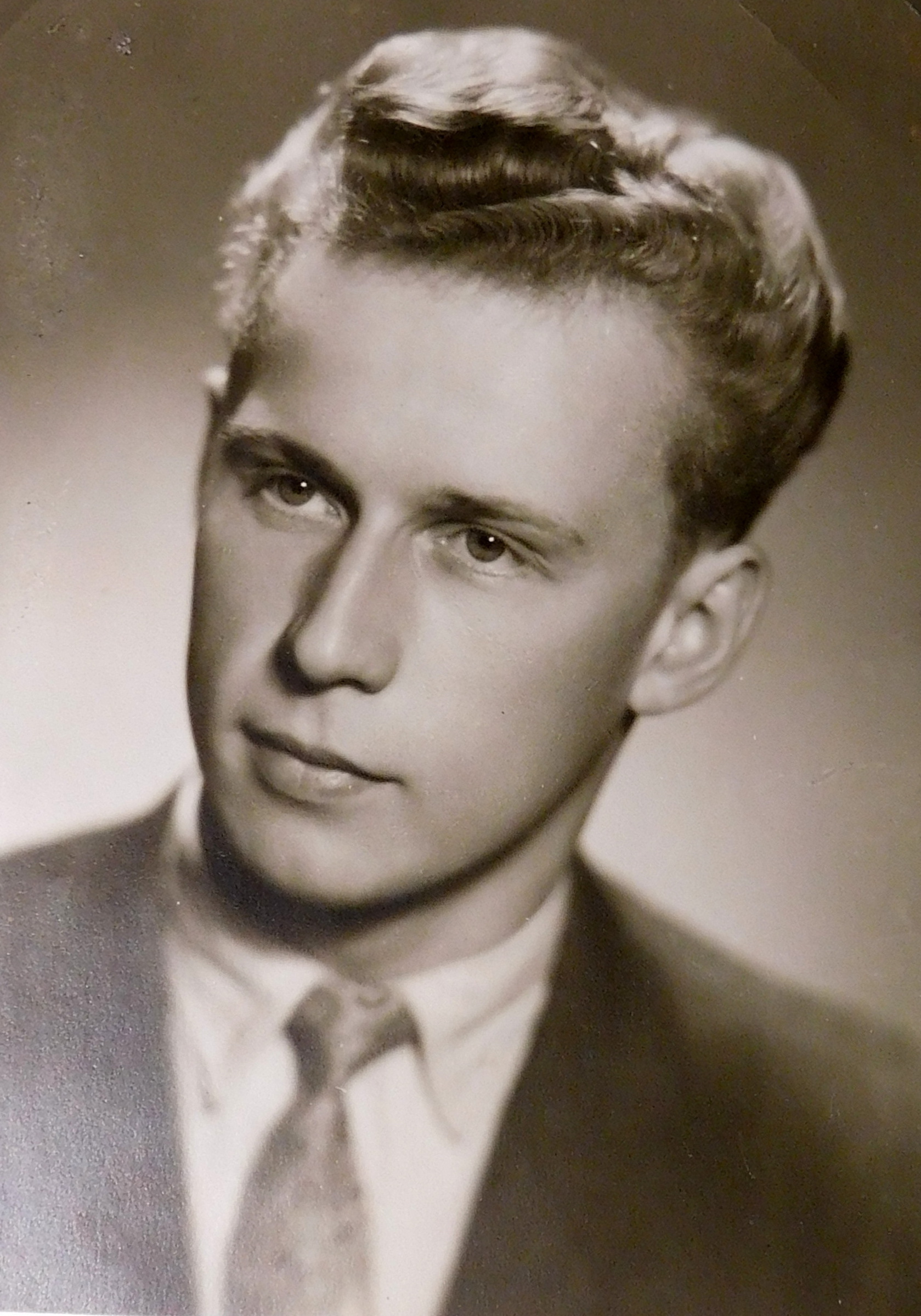

František Winter was born on December 17, 1935, on the farm No. 86 in a village called Malá Morava (Klein Mohrau in German) as the eldest child of parents of German nationality. His parents owned a farm in the village with twenty-one hectares of agricultural and forest land. Since early on, he had to help his parents with farming and his childhood was mainly connected to work. His father spoke Czech very well and was very well connected and familiar with the Czech environment. That might have been one of the reasons why he disliked the Nazi ideology. His son Francis recalls that he had a lot of trouble under the Nazi occupation. In April 1946, the family was excluded from the expulsion of Germans with the promise that they would be able to stay on their farm. However, after just a month and a half they had to leave because their house was chosen by one of the new settlers. They could not even finish lunch when they were called on to leave. The new owner of the house plundered the house in ten years and later the house was torn down by engineer troops of the Czechoslovak army. The family then had to move several times before it could settle in nearby Vojtíšková. In 1959, František Winter married and moved to Hanušovice, where she still lives today.