Bibiana Wallnerová

* 1932 †︎ 2014

-

“Once, the members of the Vlasov army came and as they didn’t need an interpreter they told us in the evening that we would be placed to the wall next morning. However, that night they ran away on their toes, because partisans let them know somehow that they would shoot them or the like, so they fled. In the morning, we should have been executed, but they weren’t there. I tried to assure my mum, ‘Mum, don’t be afraid, it doesn’t hurt and it also doesn’t take long.’ I can imagine how much she lighted up.”

-

“Everything was done in secret; we didn’t say anything to anybody as we couldn’t do so, neither to our friends. We left our stuff there. I only gave some things to my friend. Maybe she knew it even though we didn’t say anything aloud. I also gave some carpets and china and the like to my piano teacher. However, the majority of our things stayed in our flat, just not to create suspicion, to prevent comrades from searching for the missing things. Everyone took only one backpack with their stuff.”

-

“We were there along with my sister for about a month. Actually, we worked there for several weeks as interpreters for Seppo Klimt, who accommodated us at the peasant’s house, where he also lived and once, a daughter of our old acquaintances from the village of Rybie, Erika Strmeňová, a twenty-year old and single girl, came to tell my sister that she had met our parents up there. And I regard this girl, Erika Strmeňová, as a really brave person, because it was not a big craft to shoot hither and thither and to raise revenge from the Germans. Every person having a gun did it. However, bringing some bread to starving people, almost dying of hunger, and helping them survive and informing people of their situation was a real bravery worth the effort.”

-

“Suddenly, soldiers started to shout and released the fire. Just, ‘Freeze!’ they spoke Slovak quite well. Thus, I and my sister lay on the ground while they were shooting, but our father shouted, ‘Kids, put your hands up!’ and I thought, ‘Certainly and how will I play Chopin’s nocturne without hands?’ So I lay there and said myself that I wouldn’t raise my hands until my sister would do so, because she was my role model, she was my heroine, and she also was a partisan. Thus I decided not to move until she would do so, in no case. I lay right in front of her. I was laying this way there and my sister behind my back. Soldiers approached to us, they were swearing horribly and lifted me up and said, ‘Comrade, I don’t know, lieutenant, or such rank, we report the four arrested and one dead.’ Vili was not there. We were among those four arrested along with some Mr Bublinec, who I hadn’t known before and who came with Vili, and that one dead person was my sister.”

-

“We had nothing. There were no foodstuffs, no clothes; we were hungry, because at the end of war we only got some rations. Then, after the war people used to exchange their old clothes for foodstuffs with Hungarian women from Žitný ostrov (Rye Island). However, we had nothing to offer for exchange. We got a pair of shoes from UNRRA and I shared them with my mother. Those shoes had a sort of fur on the top and my little finger jutted out of one shoe and thumb of the other. Probably some noble Americans sent them. Thus, when my mum went to town, I had to stay home and vice versa. Fortunately, at the beginning of the next academic year I got new shoes, very nice ones made of pork leather. I was really proud of them.”

-

“I was alone in a room when they came to take me for an interrogation. They blindfolded me and I never knew what would wait for me there, but I noticed that there were three different investigators. One was really bad, I was in danger of violence and I could easily get some claps, the second one was strict but fair, and the third one was young, handsome, and quite friendly. I was aware of their common objective, which was getting as much information from me as they could. They wanted me to reveal and involve other people. You know, we didn’t need to hold back that we had wanted to cross the borders since they had caught us there. In this regard, we had nothing to conceal, the only thing they didn’t know was who had known about the escape and who had organized it. However, I knew nothing about it, because it was organized by my parents, actually by my father and sister. So then, when I had to choose one of those investigators, I chose the young, handsome one, who was nice, because I thought talking to him would be much better than talking to the other two, who always threatened me. I posed as a martyr and it was my best acting ever, because I was aware that if I had sulked and pretended being a sort of hero, they would have beaten for example my father up. My relatives actually were my hostages. I couldn’t do anything wrong. Therefore I chose the young and nice one to be my investigator. I fared quite well as I tried to react to him. I was willing to talk to him and talk to him honestly, so we made a sort of friendship. There were moments when I felt shakily and insecurely about not telling them everything and keeping it back, because I am not a type of hero, I don’t know how it would have been if they had tortured me, but fortunately they didn’t do so. I assume there were many various factors playing an important role; I mean that they knew everything about me, that we lost my sister, and also that I was willing to cooperate with the young investigator. The fact is that either before or after the trial anybody else was arrested in connection with our case.”

-

“The times were unsettled and people had to face so many troubles. A lot of them from our neighbourhood had been arrested and nobody could say a word. If I wanted to tell something to my friend, I only could do it in the middle of the schoolyard, because we knew there were no microphones, no walls or something similar, I mean no other ears listening to our conversation. Only there we had a good view of the whole yard. All the other places were full of narks and informers and the like.”

-

“When I was released from Sučany, I remember I was standing in front of the gate and didn’t know where and which way to go. I had no idea of the value of money; I had no idea about the town or village I was in. And some little boy passed me on his bicycle. And I told him, ‘Can you see me to the train station, please?’ I wanted to go away. And the boy said, ‘It’s over there.’ I responded, ‘You know, I am a stranger here, I have just been released from here.’ Then, the boy went about twenty meters before me on his bicycle, he didn’t want me to get closer. He even took my package on his bicycle as it was heavy and the weather was warm, but he didn’t let me approach him. I didn’t understand his attitude at all. He was about fourteen years old. Probably I presented something very dangerous and bad. The problem was that the amnesty was proclaimed about three weeks earlier and all those criminals were suddenly released from prison and aroused scandals in Sučany, they got drunk in the first pub, chased men, and elicited unrests in families. And as I was coming from prison as well, of course, he couldn’t let me come nearer to him.”

-

“My sister wanted to leave, my father didn’t want to. He told us in 1948: ‘Children, let’s go away.’ But we answered: ‘This is our home. We are Slovaks and we want to stay here. Once it is sufficient for others, it will be for us too.’ This was our background. So he said: ‘Look, it was my proposal, but if you don’t want to go, it is up to you; you have decided.’ Three years later my sister insisted: ‘Let’s go, let’s go, let’s go!’ She became friends with children of the former minister of the foreign affairs Bohdan Pavlů. They had escaped and sent somebody to help us. They sent a double agent for us. Of course, we didn’t know that.”

-

“There we stayed approximately for two weeks. I don’t know exactly how long we were there; I guess it was like ten days, two or three weeks. I know they placed there one border guard, who tried to give me a look of how much he likes me, etc. It was an informer who was supposed to get some information from me. He visited me and did few favours for us, so when I saw he sympathises with us, I asked him for a towel, tooth brush and tooth paste. He took care of that, probably it was covered by the state costs. He looked like if he was boiled down in a decolorizer, so blond he was. We used to call him the good soldier Švejk. Such people did not introduce themselves, but as they behaved in certain way, we gave them our own names. For example, one man we called Puťdarožka, because he used to whistle: ‘V puť darožka, frantavája...’ Or we called him Franta Vája, what sounded quite Czech, although it wasn’t. According to how the people coughed or shouted, or what songs they sang we named them. Each of them had certain feature. This good soldier Švejk used to come to me and say what a good girl I was, that he’d liked to have a date with me and so on. Finally he said he could have saved something from our property. It was obvious that this was nonsense, because I knew the State Security members have sealed everything up and for sure they pounced on it. Right, he would surely get there! ‘What would I like?’ ‘I don’t know. Nothing is so interesting for me to put such a good man like you into some kind of danger! No way. ’ And he said: ‘You know, if I brought that to you, you would have to tell me name of a really good man to whom I could hand it.’ ‘But I don’t know such a man!’ Then at night he was in charge and at two, at four o’clock there were situations like from Romeo and Juliet. Me behind the bars in a white blouse, striped by the bars, the moon was shining; he – the good soldier Švejk - standing in front of the bars with bayonet persuading me to think it through and to ask my mother. He repeated: ‘A really good man I would need there, because otherwise it didn’t work out.’ ‘Firstly, I don’t know what could you save from there and secondly, I don’t know any man which I could mark for you.’ Well, so one more night he came and it ended up with failure for him. This was when I understood what he really wanted while being in charge. It was not about my pretty blue eyes!”

-

“The man brought us a message from the Pavlů family. It was a picture tore in half while they had one half and we had the other one. This we considered to be an adequate identification. We packed up and went. We packed all we could carry and what we couldn’t, the other ones plundered. Not all, but while we were leaving, they packed our stuff too. We didn’t care though, as we knew it would stay uncared-for anyway. Although, I really minded seeing an ugly man, bent down and packing our blankets and carpets. My sister was neither indifferent when she saw those people. She said: ‘Somehow I even don’t want to leave anymore. I am quite worried.’ And I hissed at her: ‘You should have thought about this before.’ And actually, this was morning of the last day of her life. I haven’t suspected it at all, though.”

-

“Leopoldov was such an investigation reign of terror. I was there only with my eyes covered. They came to pick me up for the investigation and took me away. Leopoldov was one really haunted place. I had to listen how for example Janka Guzová (the singer) belted out into the loudspeaker. The music blasted out the whole day so that no one could hear what was really going on there. From time to time I used to hear some lamenting or screams. Once I even heard to cry my own father. Nobody could dissuade me from thinking it was him. They yelled at him: ‘Talk! Talk! Talk!’ ‘It was my poor daughter, please, understand!’ He cried. This way I knew it was really him.”

-

“That was horrible. Firstly I didn’t know whether I was in Austria or in Slovakia. They shouted: ‘Stop! …’ So that’s how I knew I wasn’t in Austria. It was so cruel and loutish and I said to myself I would not get up. We lay down when the shooting went on. We were defenceless and they kept shooting at us. In front of my head I had a bag in which was a coat. This bag hit my head, yet, later on we found a slug, a bullet, which bored itself into the coat. So, it wasn’t my destiny to walk the way of my sister, although I didn’t know my sister went this way. I thought since my sister wasn’t detained with us, she would have stayed there and crawled away. She wanted to go to the Pavlů family, I didn’t. Then I heard a report: ‘Comrade Officer, I report four detained and one dead.’ We looked who else went with us. There was a man who joined the same group, but I didn’t know him. So there were three of us, four in total, but who was the dead one? ‘Who is the dead one?’ My father asked: ‘Who is the dead one?’ And my mother asked as well: ‘Who is the dead one?’ Afterwards we came to know it was my sister, twenty four year-old; a promising candidate of law degree. We didn’t want to believe. I let them show her to me… and yet I came to believe.”

-

“In those years I think they judged just by throwing the dice. Anyone could get ten, twelve, fifteen years. I only got such a small sentence because I was so young and actually, they didn’t have any evidence against me except the fact I went there with my parents. Even though I tried to argue with the prosecutor that I was the main culprit because before the trial, the man detained along with us said: ‘You and your father are the guilty ones.’ So I was determined to plead guilty and to take the blame for it all. But the prosecutor proved I wasn’t right, and since I was so cheeky, he didn’t give me only few months like he originally planned, but two and a half years.”

-

“It was horrible; we were completely petrified, totally dead. At first they yelled at us: ‘Stop! Stop! Stop!’ And our father shouted: ‘Children, put your hands up!’ I thought: ‘Yeah, right, I will put my hands up in such a shooting. And who shall play Chopin?’ I didn’t put them up, however, later I speculated that since our dad appealed to us, we should have listened, but my sister pulled my leg and said: ‘Don’t be a goof!’ So I told myself: ‘I am not a goof’ and I lay there. I didn’t even notice that my sister died meanwhile. I said to myself: ‘Unless she puts her hands up, I won’t.’ She hasn’t done that though. When the men, the guards came, they picked me from the ground with a huge swearing. As they picked me by force, I let them do that. We were completely petrified, half-dead. How would you be in such a moment? Then they took us to a guardhouse, where they stripped us naked. There was also some policewoman who took from us everything what sparkled. Our ear rings, she took even my mother’s wedding ring. All what they saw, they seized without any record. What a profitable job it was for them!”

-

“I have never come back to a normal life. Normal life for me would mean being at home, with my parents and attending school. There was no school for me, no home for me and my parents were in jail. When I managed to find a job, I worked way overtime so that I could have Saturdays off, because it was a work day on Saturdays as well. I wanted to do that to be able to visit my parents on Sunday morning, and this way I could travel back and forth. Once in two months I was allowed to visit each of them, meaning that once I could visit my dad and once my mom. I had to be really thrifty to save money for the journey and some overtimes to have a half day off. This was my sense of life. I lived in this from June to April, when my father died and then until the next July, when my mom was released. This had nothing in common with normal life.”

-

Full recordings

-

v Bratislave, 11.07.2011

(audio)

duration: 02:41:48

-

v Bratislave, 09.08.2013

(audio)

duration: 01:56:06

Full recordings are available only for logged users.

There are so many things a man doesn’t need

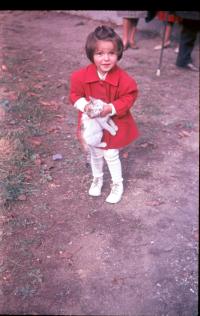

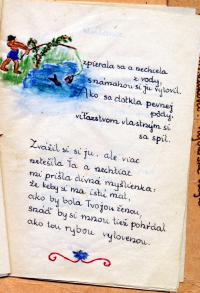

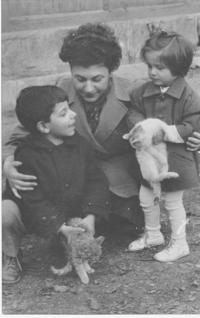

Bibiana Wallnerová was born on December 14, 1932 in Bratislava. Along with her sister Dorota she grew up in cultural environment. Their parents led them to love sports, foreign languages and music. Yet as a child she was confronted with the cruelty of war and after the February 1948 also with the brutality of the communist regime. Bibiana’s father in the same year proposed to his family to flee abroad, however, both daughters refused it. Three years later the situation changed and thanks to the older sister they obtained a contact to a smuggler, who would guide them through the Iron Curtain. On May 9, 1951, shortly after 2 a.m. everyone was detained by the Border Guard near the wire fence app. 500 m from the passport control in Kopčany. There was shooting which ended life of Bibiana’s sister. Bibiana and her parents were taken to a guardhouse, where they were deprived of all their valuables and consequently they were put to barracks of the Border Guard in Malacky manor house. Here she stayed with her mother for two weeks, after which they moved her to Bratislava prison at Špitálska Street called U dvoch levov (At Two Lions). After the investigation she was placed in Leopoldov prison and later on into the cell of county court. She spent several months in solitary confinement. In a trial that was held in September 1951, her father was sentenced to twelve years for high treason, her mother got five years and Bibiana, accused of “only” attempt to cross the borders was sentenced to two and a half years. Together with her mom they were transferred to Ilava prison, whilst her dad was sent to Leopoldov. Yet in 1951 the women’s penitentiary was moved to Rimavská Sobota; furthermore in April 1952 Bibiana had to move again. This time, however, she was definitely separated from her mother. With some of the women prisoners she went to Sučany, where she became friends with Maruška, a talented poetess who came from Bohemia. Together they created United Poetical Singing and Artistic Association, and after their surnames they named it SOBKOV.

In May 1953 thanks to the amnesty she was released, however, nothing resembling a come back to normal life awaited her. She got employed in laboratory equipment in Bratislava as a correspondent, although she tried to subordinate everything to her only aim - visiting of her parents in the prison. Since her mother was in Pardubice and her father in Ilava, and later in Mírov prison, it was very time consuming and financially demanding to travel to visit them. Only the love towards her future husband gave her strength to live on. It took her years to manage to gain a flat. After her first child was born she stayed at home and besides taking care of her family she started to build up her literary career. She composed songs, cooperated with various music composers, won many competitions, she proved her ability also as a translator and later she worked as a tourist guide in Čedok company. She earned name of a great author, even though her past oftentimes caught her up and deprived her of her work. At last Bibiana got a job in radio, in the editorial department for children and youth, where she prepared successful music programs. In spite of the fact that they fired her from this job, after some time she gained the job back again. Bibiana Wallnerová has been still active in her literary work. She has been author of several books. Her experiences of the prison life are described in a novel called Pod basovým kľúčom (Bratislava 2010), from which one can feel a great sense of humour and resistance, with which she fought against the inauspicious destiny.