Three hundred and ninety-five years in the village of Kosov

Download image

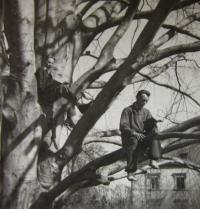

Jan Vaňourek was born October 23, 1936 in Václavov near Zábřeh na Moravě. He spent a large portion of his life in nearby Kosov at the family farm, which their ancestors had allegedly owned already since 1635. At the end of WWII, prisoners of war guarded by Germans on their march westward were accommodated in their barn. Later the barn also served as accommodation for the victorious Soviet army. After the communist coup d’état and the forced collectivization of the countryside the family faced enormous pressure which consisted in obligatory deliveries of agricultural products and prescribed quota which were nearly impossible to meet. In 1951 Jan Vaňourek was expelled from agricultural school and together with other children of so-called kulaks he was sent to work to Vlčice which was administered by the state farm in Javorník. After his return he managed to complete his studies and after several protests against declined admission he was eventually admitted to study at the Agricultural College. The unified agricultural cooperative (JZD) was established in Kosov as late as 1957. At that time, Jan’s father already knew the repercussions for farmers who had insisted on continuing to work independently, and he rather chose to join the cooperative just like everybody else in the village. When he graduated from the college, Jan Vaňourek focused on horse breeding. He worked at the stud farm in Tlumačov and later in Napajedla. In the end he was even offered a position in the general directorate, where he was in charge of horse breeding in all of the Czech Republic. After the fall of the communist regime, he and his wife Věra returned to the family farm where they live now.