They’d like to hear just a symbolic: something bad happened, we’re sorry. Nothing more

Download image

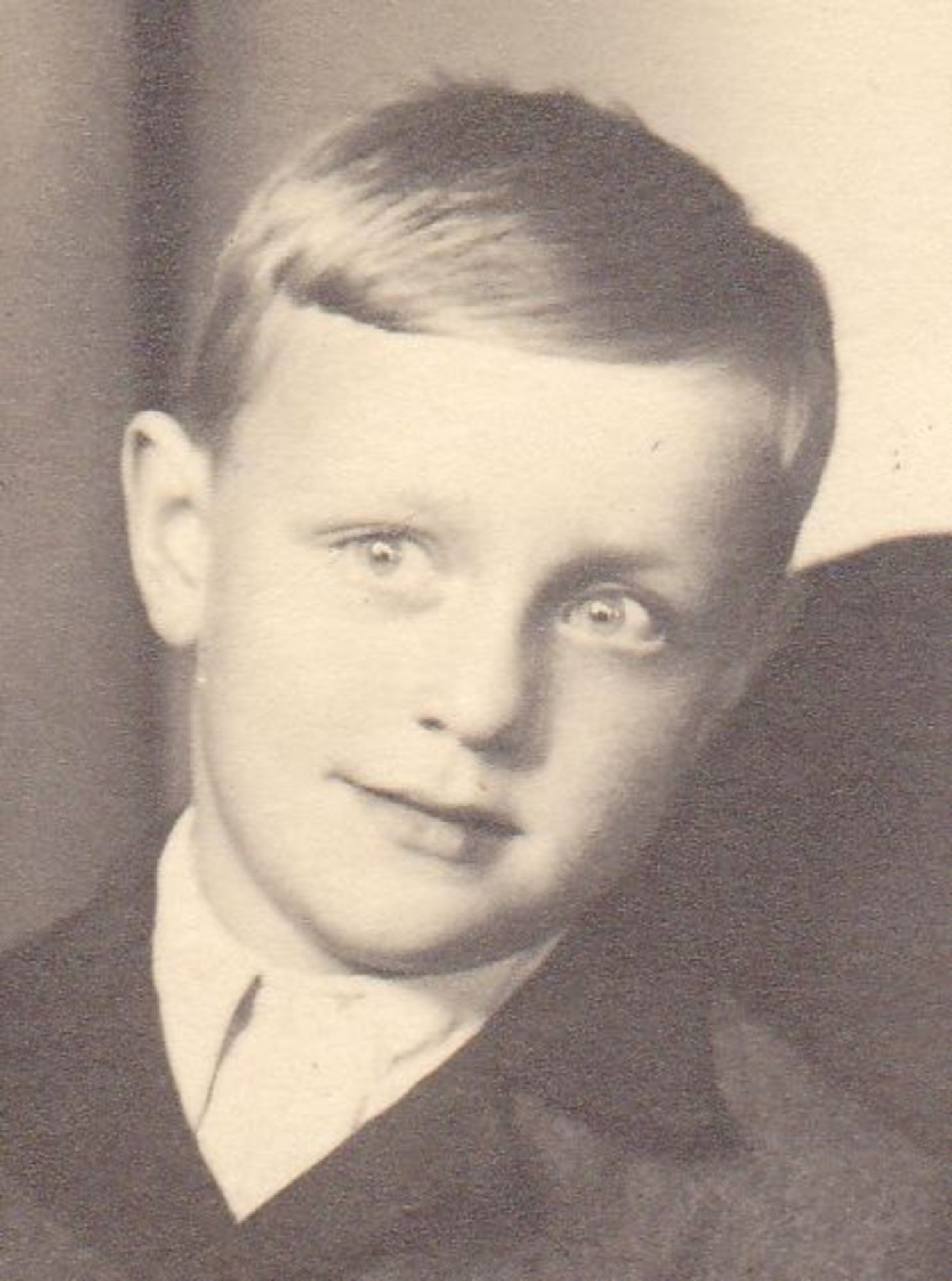

Egon Urmann was born on January 18, 1945, in Lenora into a family of a German glassmaker. The events associated with the end of WWII radically marked his future life. The family of the skilled glassmaker managed to avoid expulsion but in the autumn of 1947, they had to move to the inland of Czechoslovakia, to a place called Včelnička near Kamenice nad Lipou. After two years, they were allowed to return to Lenora only to find their house in ruins, completely devastated by its new owners. It took several more years before they were finally able to buy their own house back. Meanwhile, the family tried several times to apply for emigration to Germany, but never succeeded. Due to his German origin, Egon was prevented from studying and thus he chose an apprenticeship as a car mechanic. After completing it, he worked for the ČSAD company. After November 1989, he also worked for some time in Germany. Nevertheless, he would always voluntarily return back home, as he did in the past. Until today, he’s keenly interested in the history of the Czech-German relations and seeks to contribute to their improvement. He recalls a number of interesting stories about his parents, relatives and neighbors from the end of the war and the period following it.