We should forgive, not forget

Download image

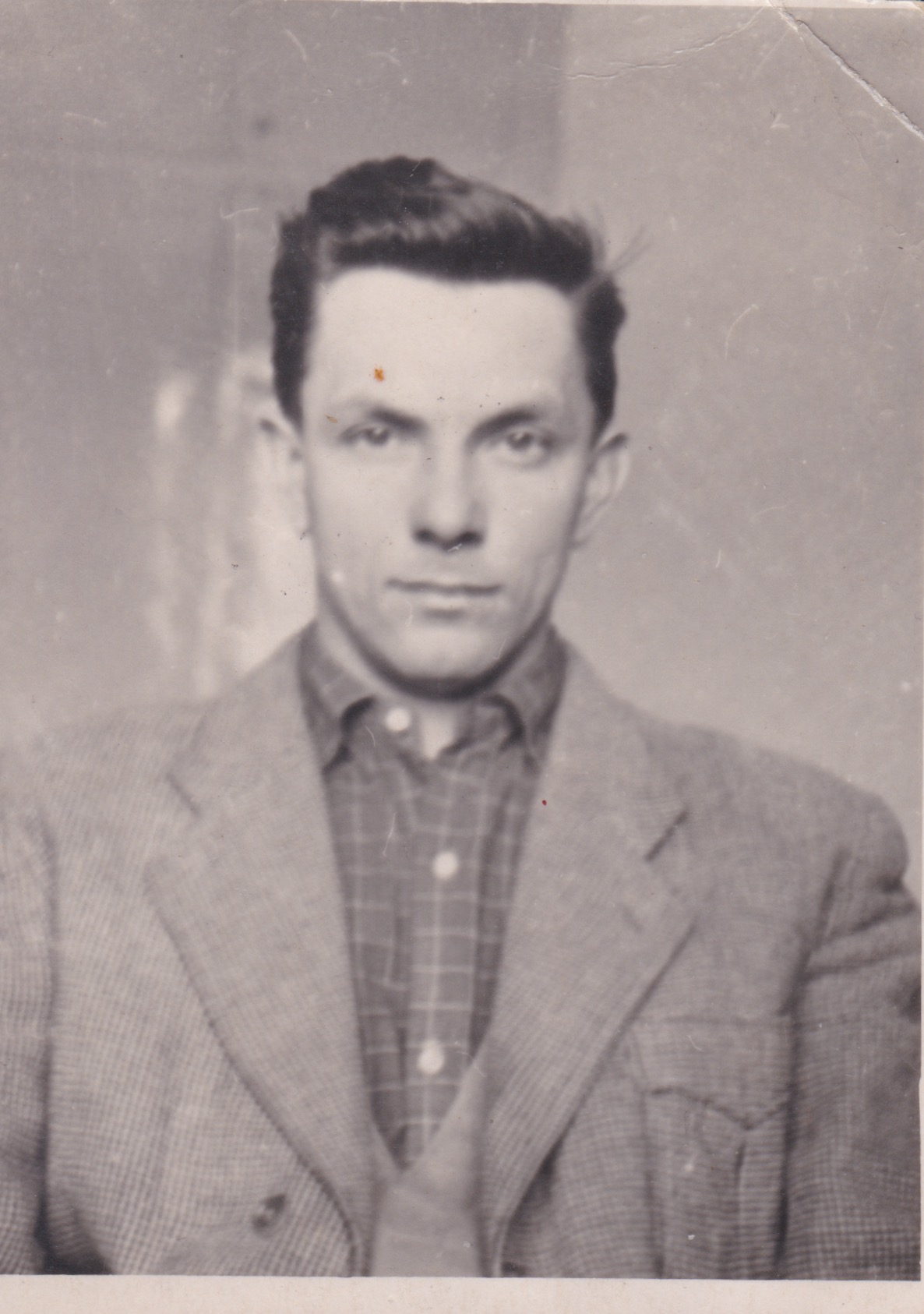

Josef Trpák was born October 15, 1935 in Pacov where his father Jan ran a fine leather products business. In 1947 he finished building his own factory where he then moved with his family of seven. Apart from business he was also engaged in the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party and in the Sokol movement. In March 1949 his business was nationalized and the manufacture was transferred under the KOZAK factory. His father then had to start working as an unskilled bricklaying laborer and later worked in a brick factory near Hrádek. The family was displaced to a farm in a nearby village Cetule in June 1950 and Josef’s father was sent to work in the Ostrava coal mines in October. After his return in March 1951 he started working as a farmer at the farm in Cetule where he was trampled to death by a horse in June 1951. Josef’s younger siblings were temporarily sent to stay at their relatives’ after this tragic event. Only Josef and his brother Jiří stayed with their mother Emilie. They moved to a former parsonage in Zhoř in November 1951 thanks to the help of the Pacov priest Ferdinand Kondrys. Josef had to start a coppersmith vocational training in the Pacov engineering works because of his class origin. After completing his military service he was proposed to work in the Příbram uranium mines which he accepted under the condition that he would be able to study a secondary technical school in the evenings. He worked at the mines together with convicted political prisoners from the Bytíz and Vojna camps. After the one-year “coal brigade” he went to ZVÚ in Hradec Králové where he successfully completed his high school education and returned to Pacov where he got an apartment condominium with his wife and where he started working at a technological institute in 1964. Ten years later he was named head of production engineering by the company’s director but after only two years he was laid off in 1976 due to a negative complex assessment in which he was characterized as having a hostile attitude to the socialist system. It was hard to find a job with such a bad assessment. He finally landed in Sigma Modřany where he was elected to the union presidium in the spring of 1989. As the chairman of the union he took part in the general strike in Temelín in November 1989. He has raised three kids with his wife, all of whom couldn’t get an appropriate education because of Josef’s political assessment. In 2020 Mr. Josef Trpák lived in Pacov.