The ionosphere is the ionosphere, and there’s nothing you can do about it, he explained to the secret police

Download image

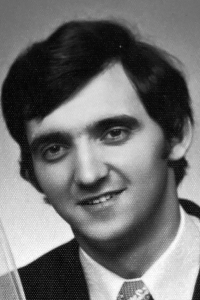

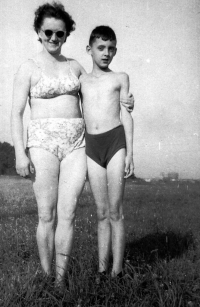

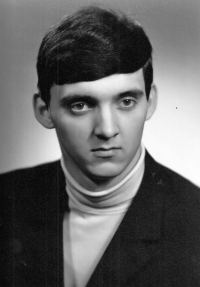

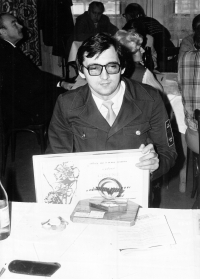

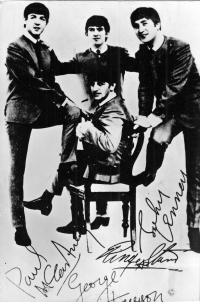

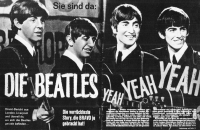

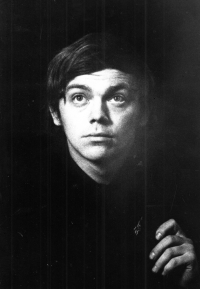

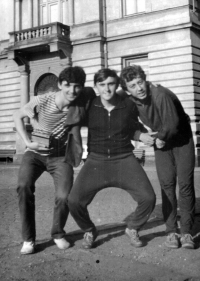

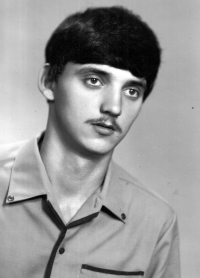

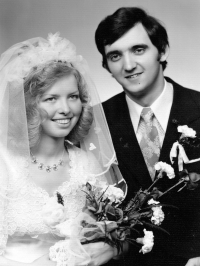

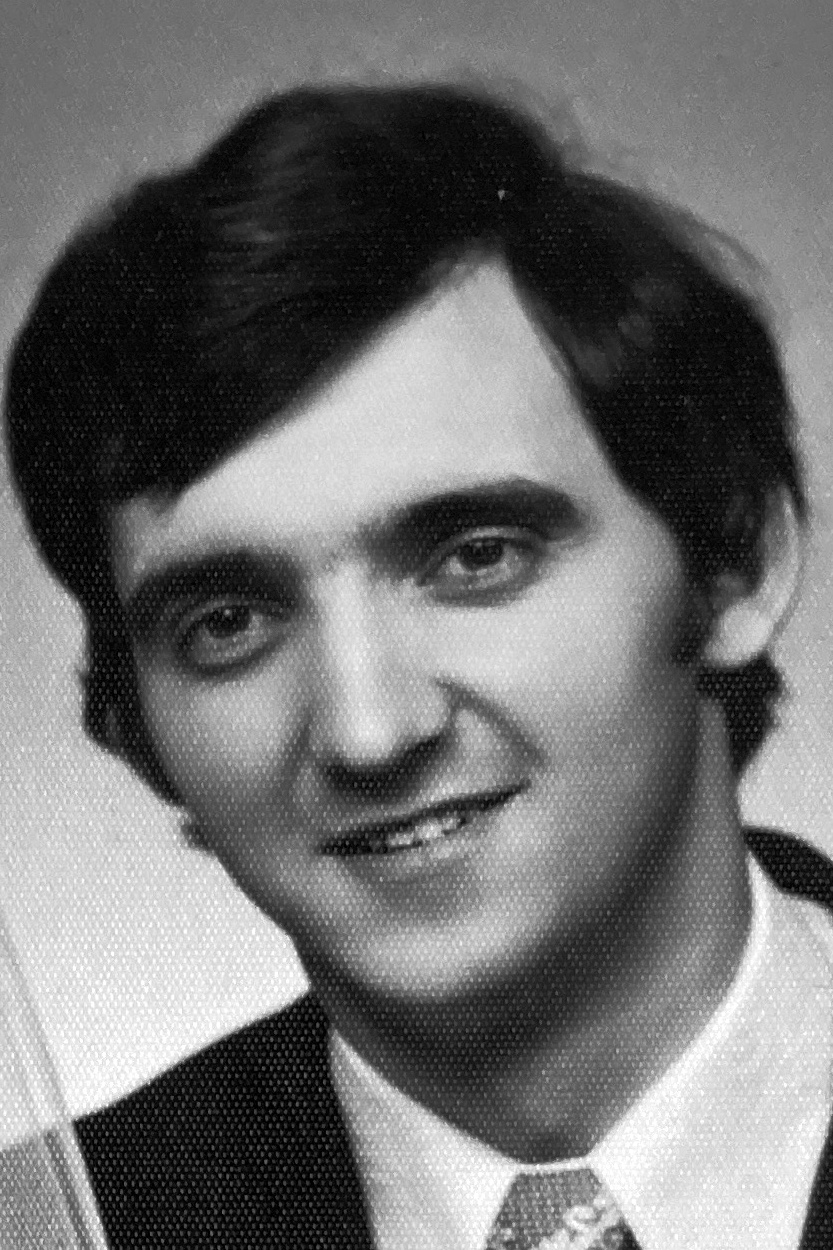

Jiří Tieftrunk was born in Olomouc on 6 July 1951. His mother Vlasta née Marková completed a medical school. His father Jiří worked on the railway. At age six, Jiří Tieftrunk moved with his mother to Ostrava and then to Havířov. He completed a railway high school in Česká Třebová and worked as a station technician. After work, he did “deixing”, i.e. hunting for shortwave broadcasts from stations all over the world. He also listened to foreign radio broadcasts in Czech, especially RFE. He wrote letters to stations behind the Iron Curtain, focusing on music shows. He was interrogated by the State Security Service (StB) which filed him as a person under investigation. He gained a detailed insight into the system using which the communist regime jammed the broadcasts its so-called hostile stations. Since the 1990s, he has authored radio music programmes, mainly at Czech Radio Ostrava. Jiří Tieftrunk lived in Ostrava during the filming for Memory of Nation in March 2025.