I’m glad I’m not afraid of confronting evil

Download image

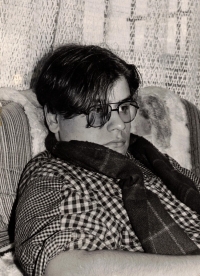

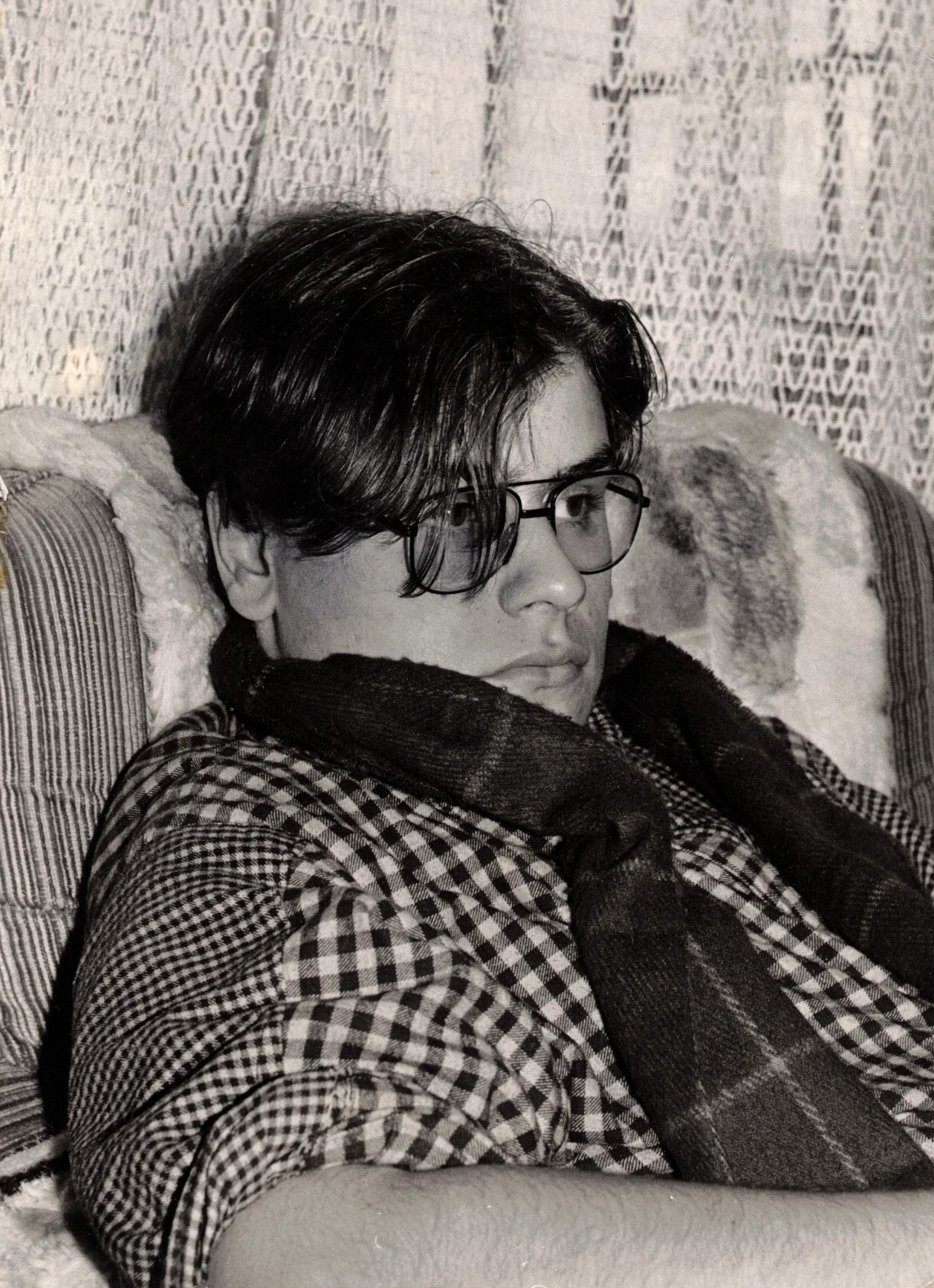

Ondřej Tichý was born on March 13, 1972 in Pacov, but since his childhood he grew up in Tábor. His father Ladislav Tichý worked in security corps - his son Ondřej depicts him as a really straight person with a sense of justice, who experienced severe dilemmas during November 1989. Shortly before the November coup, 17-year-old Ondřej Tichý visited the Federal Republic of Germany and was delayed due to car problems. The headmaster of the grammar school, who thought he had emigrated, had the students vote on his guilt in his absence. In a situation where he was threatened with expulsion from the grammar school, Ondřej Tichý plunged into the whirlwind of revolutionary events. He printed and distributed materials, met people, spread information around. The highlight of his activities in support of the revolution was the “occupation of the school radio” - on the day of the general strike on November 27, 1989, he and his friend occupied the staff room of the Tábor grammar school. Ondřej Tichý is the father of five children and an officer of the Army of the Czech Republic, as a pyrotechnician he participated in missions in Iraq and Afghanistan.