Dad said it would all be over in two years’ time and they’d give us the company back

Download image

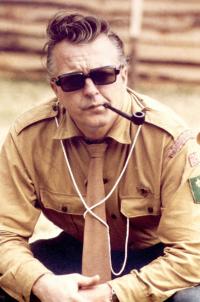

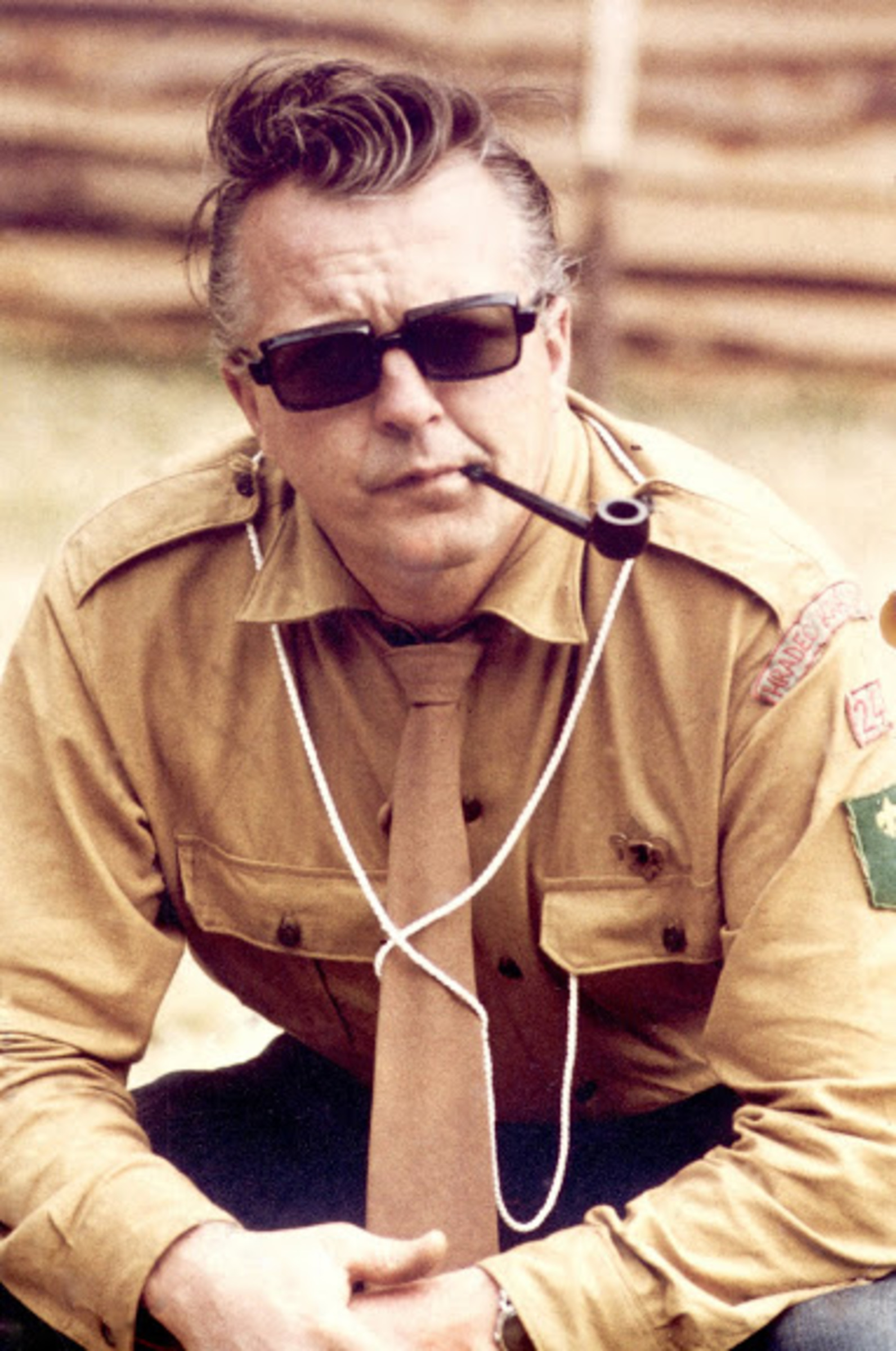

Milan Štěpánek was born on 1 August 1929 in Dobřenice, a small village in eastern Bohemia, near Hradec Králové. His father was a successful businessman from the 1930s. The family firm dealt with the processing and distribution of wood, but it also traded with coal and built single-family houses. The Štěpáneks also owned a coffee roasting business, a chicory plant, and a transport company. Their enterprise was nationalised before February 1948. The witness studied at a business academy. He was then supposed to start work under his father, but the company was nationalised only a few weeks after he was employed there. His father Milan Štěpánek was sent to a forced labour camp in Pardubice. In the meantime his son had to find himself a new job. He became a wood buyer for the state enterprise Lesy (Forests). In 1951 he was drafted into compulsory military service and assigned to the Auxiliary Engineering Corps (AEC; forced labour corps), which he had known nothing about until then. After boot camp he was variously allocated to units in Děčín, Tábor, Trenčín, and Ostrava. After returning home he worked first as a coal miner, and then as a driver for Ingstav (an infrastructure construction company). From 1968 he worked in the sales department of a furniture firm, and his last job was as an inspector of the sale of musical instruments at Melodie.