The key is not to whine

Download image

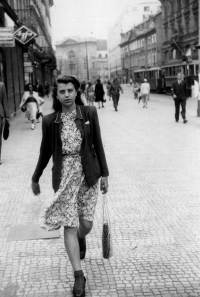

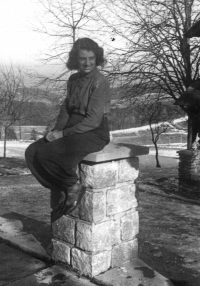

Eva Šteklová was born January 22, 1928 in Prague. Her parents Theodor and Metodějka Lipovský came from the Haná region but moved to Prague shortly before Eva’s birth to be better off economically. Both of them were cotters who helped farmers with harvesting and in winter they worked in the sugar factory in Kojetín. In Prague they lived in Michle in a small apartment with just one room and a kitchen, yet three more daughters were born there and the fifth one some years later. Father worked as a house painter, mother sewed at home and all the girls had to help out. One time they were late with their rent and got evicted from the apartment. The upbringing of the five girls was very strict. The whole family went to Sokol and the Czechoslovak Hussite Church; father, self-employed, was a member of the National Socialist Party. Eva was apprenticed as a textile saleswoman in the renowned shop Kohn & Neumann in Celetná street in Prague 1. She enthusiastically attended and exercised at two national Sokol festivals in Strahov in 1938 and 1948. During the May Prague Uprising her father fought at the barricades and her eldest sister attended to the wounded. After the war the witness left for a three-months temporary job in the newly resettled Sudetenland. Eva married her colleague Jaroslav Štekl, had two kids with him and worked at different positions in a textile shop her entire professional life. For a short period of time in 1968, her husband was the director of the House of Fashion in Prague, however as an independent he was removed from the position during the Normalization period and later worked as an economist. Both their children left to study and start a new life in the USA. Eva visited them several times. Daughter Eva became a professor of Slavonic Studies and has authored several professional publications.