I was told that my son was dead. But he was sitting next to me!

Download image

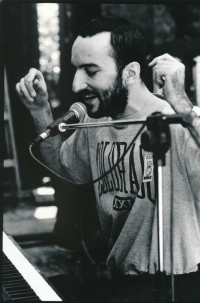

Publicist Jana Šmídová was born on 10 April 1949 in Prague. Her father, journalist Milan Weiner, came from a Jewish family that suffered from the Holocaust. He himself survived imprisonment in Auschwitz and other concentration camps but lost his brother, father, grandparents and other relatives. After the war, he worked as a journalist, but as a result of the anti-Semitic purges of the 1950s, he had to work in less exposed positions for a time. He was rehabilitated in 1963 and then founded the International Life Editorial Office at Czechoslovak Radio, which he directed until he fell ill in 1968. He died on 25 February 1969. Her mother, Marie, née Trčková, worked as a clerk. Jana grew up with her grandparents in Jindřichův Hradec until the age of ten when she moved with her grandmother to her parents in Prague. Following her father’s example, she gravitated towards the journalism profession and wrote her first journalist texts while studying at the grammar school in Přípotoční Street. In 1967, she graduated and passed the entrance exam to the Faculty of Journalism. During her studies, until the arrival of normalisation, she worked as an editorial assistant in the foreign editorial office of the Czechoslovak Radio. In the days following the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops, she participated in the distribution of anti-occupation leaflets. Many of her classmates who took part in these anti-occupation activities were expelled. She herself escaped the purges also thanks to becoming pregnant, and in 1970 she gave birth to her son Martin. She and her husband, TV editor Milan Šmíd, lived for several years in Louňovice near Jevany, where their younger son Michal (1973) was born. During the first few years of normalisation, she devoted herself mainly to her children. Later she worked as a technical editor on night shifts at Mladá fronta (Young Front - transl.). In 1983, she joined Svobodné slovo (Free Word - transl.) as an editor. In 1988, she had the opportunity to go to Chernobyl to report on the consequences of the nuclear disaster. In the days after 17 November 1989, her family was struck by a rumour about the “dead student” Martin Šmíd, who allegedly died during a demonstration on Národní třída. At the beginning of 1990, she joined Lidové noviny (People’s Newspaper - transl.) as an editor and later worked at Svobodná Evropa (Free Europe - transl.) and Czech Radio. She also contributed to the Federation of Jewish Communities Rosh Chodesh bulletin. In 2021, an album of 41 unique photographs depicting authentic life in the Terezín ghetto and portraits of its prisoners was discovered in her father’s (Milan Weiner) heritage. The album is known as Album G. T.