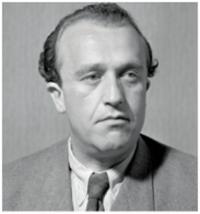

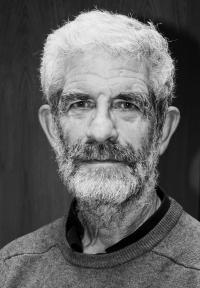

I’d be ashamed if I hadn’t signed Charter 77 back then

Download image

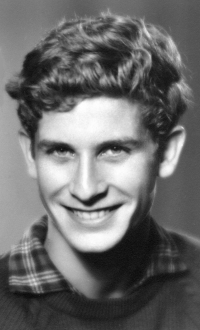

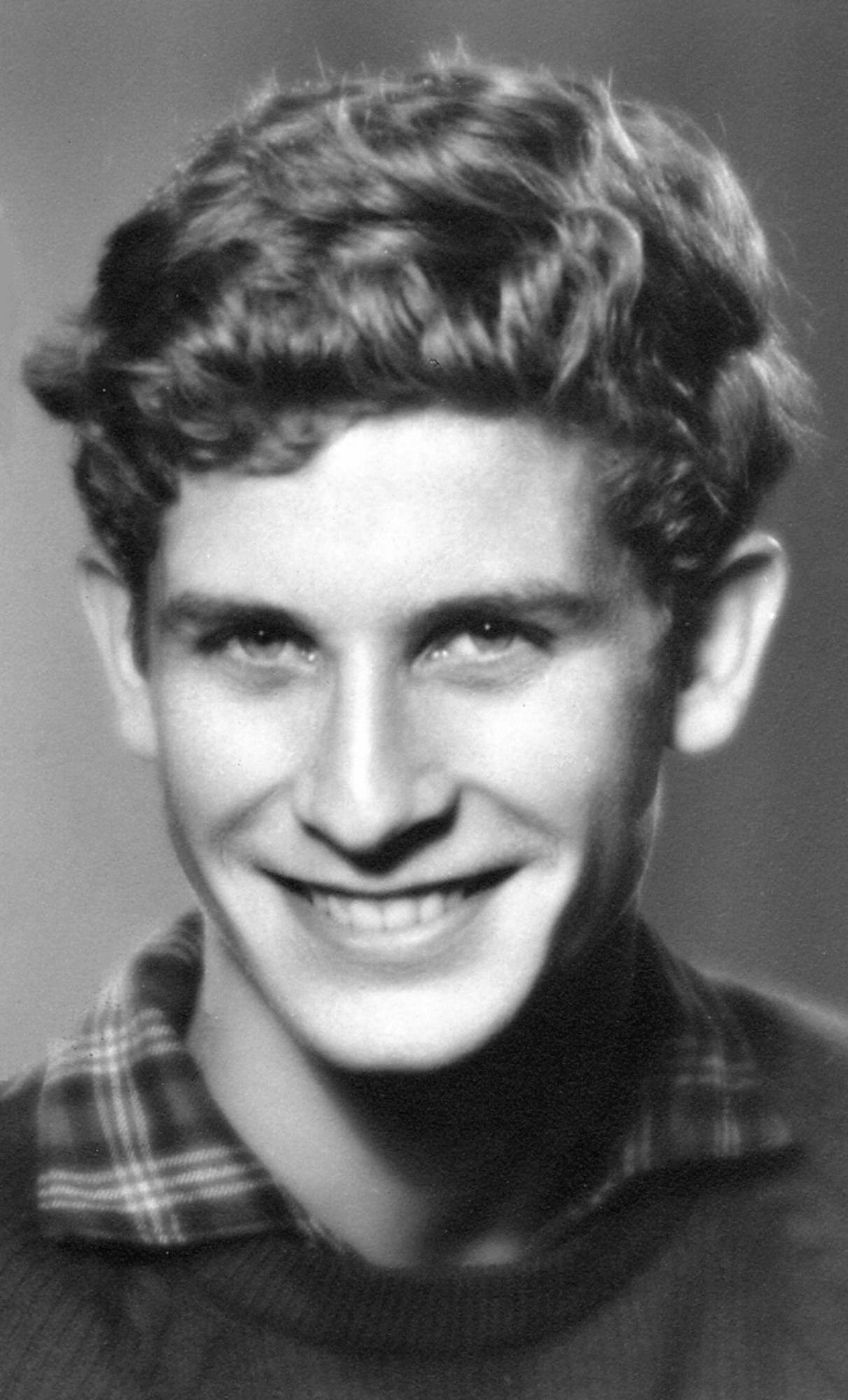

Karel Šling was born on 29 April 1945 in London. After the war his father Otto Šling took part in the political renewal of Czechoslovakia and became the regional secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in Brno. In 1946 the witness returned to Czechoslovakia when his mother was repatriated. His father was falsely accused and condemned in a show trial and executed by the Communists in December 1952. The family was persecuted, and Karel and his brother were placed in several children’s homes. When their mother was released from prison in January 1953, the family was forced to withdraw into the seclusion of the Eagle Mountains. After attending secondary mining school, Karel Šling graduated from the University of Economics in Prague. He worked at Obuna and then after signing Charter 77 at the Water Works and the Prague Water Works. In 1984 he emigrated to England; he is thrice married and has two daughters and a son.