I chose codename ‘Lhoták’, as I didn´t care about them

Download image

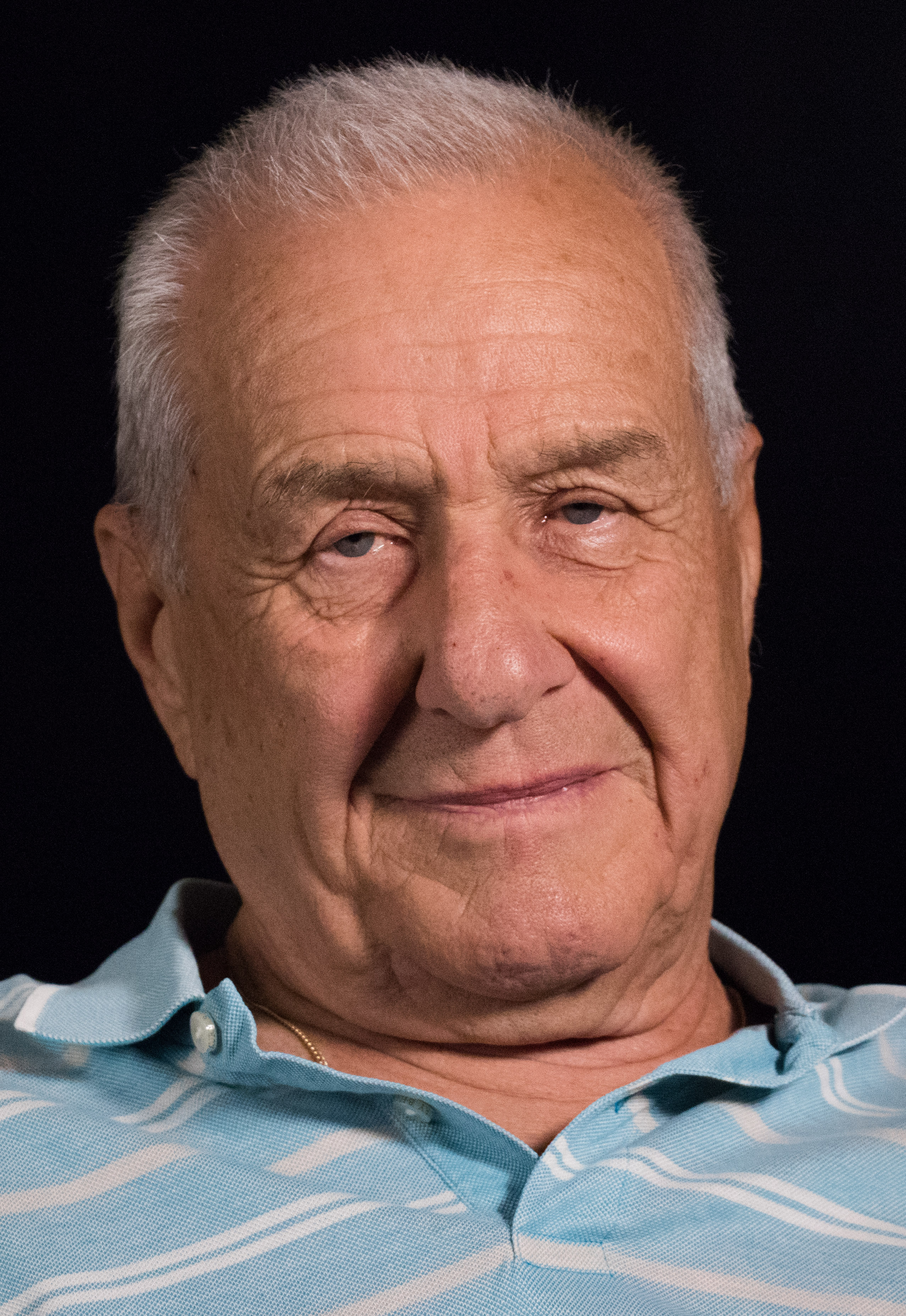

Oldřich Slavík was born on August 16th 1936 in Bratislava; before the occupation, his family moved to Prague (Praha). Despite coming from a poor family, thanks to his mother, he was able to study at a business school and to take English lessons. During his mandatory military service, he joined the Communist party (KSČ), so he would get the recommendation and could study at the University of Economics in Prague (Praha). After two years, he had been chosen to study at the National Institute of the International Relations in Moscow. He started his career at the Strojimport foreign trade enterprise and in 1968, he was sent to Tokyo as its representative. Due to the fact that he voiced his disagreement with the Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia in late August of 1968, in 1970, at the beginning of the ‘normalizations’ processes, he had been recalled from Tokyo and shortly after that he had to leave Strojimport. He had also been expelled from the Communist Party (KSČ) due to which he had trouble finding job. In the early 1970s´, he had been working as a consultant for foreign businessmen operating in Prague (Praha), due to which the Secret Police (Státní bezpečnost) had become interested in him. In 1973, he had become a Secret Police informer and had been meeting one of its members regularly till November 1989, providing them with information. After the November revolution, he had been working as a car salesman for some time, after that, he had been employed at the Interleasing enterprise. In 1993, he retired.