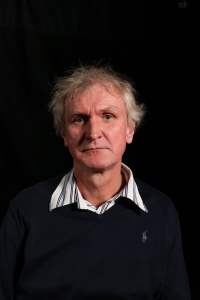

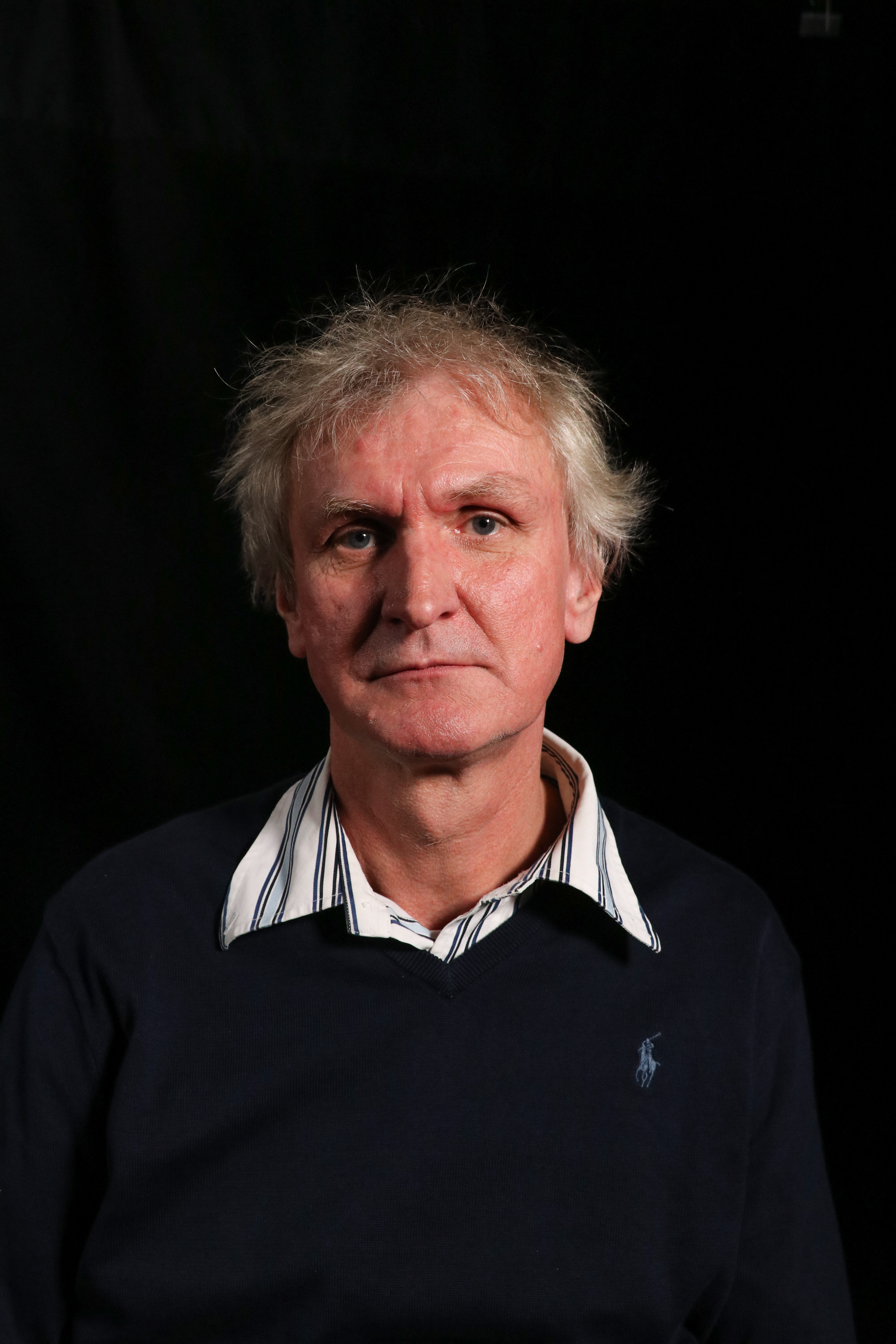

Photographer of the Velvet Revolution

Download image

He was born on 15 April 1963 in Prague, Czechoslovakia, and has been an avid photographer since his childhood. As a twenty-three years old, in 1986, he started working as a photographer for the Young World (Mladý svět) magazine – the then most popular magazine with circulation of half a million copies. A year later, he transferred to the Vlasta magazine, but above all he took pleasure in taking photos that couldn’t be published in a magazine. On 21 August 1988, armed with a camera, he attended one of the first anti-regime protests of the late 1980s and after that he didn’t miss a single one. In 1989, he took photos during the ‘Palach Week’, he captured the fall of the Berlin Wall and the student march on November the 17th. His photos of the Velvet Revolution have become well known, yet he has documented the bloody collapse of the communist regime in Romania as well. After the revolution he had been working as a photographer for the Reflex weekly magazine, documenting wars, famine, epidemics and many other topics across the globe. He won various awards for his photos, like the 3rd place in the World Press Photo competition. After 2000, he organised two fund-raising campaigns: to support children in Sierra Leone and people infected with AIDS in Ukraine.