The birth certificate had the stamp of the Jewish community, the baptismal certificate meant nothing.

Download image

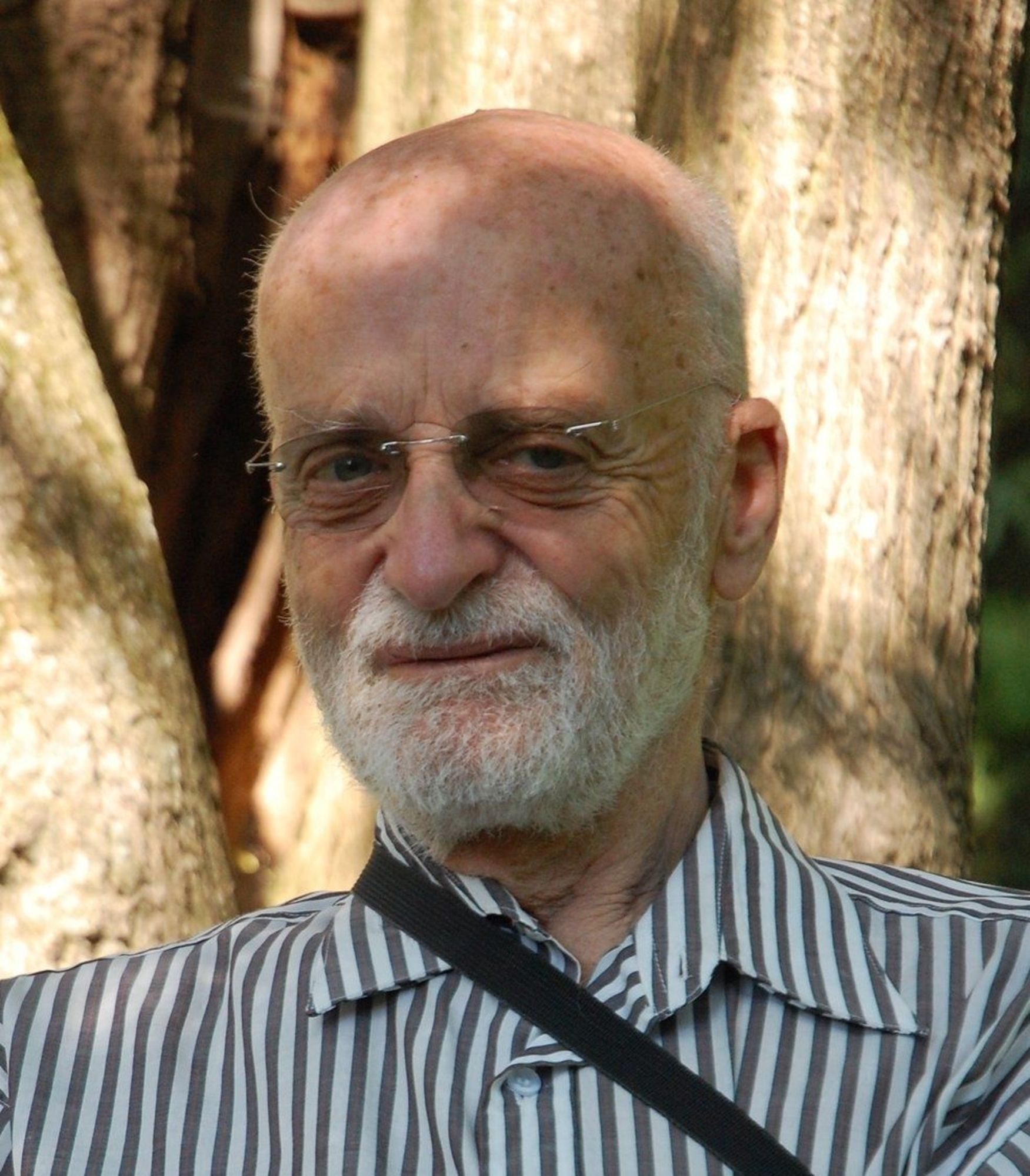

Martin Roubíček was born on the 24th of April 1930. Although he took his first breath in a maternity ward in Prague, he has always considered himself a native of Choceň. His family owned a cotton mill in the East Bohemian town, and they all lived in the “Small Palace” villa. His father was of Jewish descent, his mother was a Catholic. After the Nazi occupation, the family came under effect of the Nuremberg Laws, despite the fact the children were baptised and the family professed the Evangelical faith. In September 1941 the Gestapo confiscated the mill and the villa, and the family was forced to move to the nearby town of Holice. His grandmother was taken straight to Birkenau, where she died probably in 1943. Upon reaching 14 years of age, Martin was transported to Terezín in May 1944. To start with he lived in Jugendheim, where he escaped the wave of transports to Auschwitz in October 1944. After that, he did agricultural labour until the end of the war, like his aunt Hönigová and his two cousins. His father, Jan, protected by his mixed marriage status, worked first in Pardubice in a warehouse for goods confiscated by the Gestapo, later he was placed in the labour camp in Hagibor, Prague, before being finally taken to Terezín in February 1945. After the war, Martin Roubíček was able to happily reunite with both his parents and his siblings. The family mill was seized in the first wave of nationalisations already in 1945. Martin joined into the fourth year of an eight-year grammar school in Vysoké Mýto. Until 1948, his father was employed as a national administrator, after the communist coup however, the family decided to emigrate. An invitation from their relatives meant they could go to Argentina. Martin Roubíček did not continue in the family tradition, he did not take an interest in the textile industry. He studied medicine (in Argentina and the US), and after working shortly in the Bolivian city of La Paza, he settled down with his wife and daughter in Mar del Plata, working in the newly built hospital there. He specialised himself in endocrinology, later also in genetics, which he also taught at university. The family has set its roots firmly in Argentina, but Martin Roubíček does still visit his homeland from time to time.