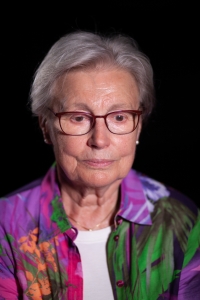

Someone had to warn us, that’s how we escaped the Ústí massacre by a hair’s-breadth

Download image

Astrid Pilz, née Hausmann, was born on 12 May 1940 in Ústí nad Labem. Her father Alfons Hausman was from a German landowning family from Litochovice (Lichtowitz in German). Shortly after Astrid’s birth, he was called to the front as a German. He and Astrid only met again when she was six years old. Her mother Ingeborg Hausman was from Prackovice (Praskowitz in German), also from a German landowning family. Astrid and her mother became indirect witnesses of the so-called Ústí massacre on 31 July 1945. In August 1945 they were deported via Dresden and Thuringia into Mecklenburg, which was in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany. Near the end of 1946 they met up with their father, who’d survived the battle of Stalingrad and captivity in a Siberian camp. Astrid began attending school in Rostock in 1947. In 1954 the Hausmanns decided to flee to West Berlin. After studying at the Free University of Berlin, she married the physicist Walter Pilze, also expelled from Czechoslovakia, and gave birth to a daughter. In 1963 she personally attended the speech of US president Kennedy in a divided Berlin. For her husband’s job they moved to Munich in 1969, where Astrid Pilz taught at a local grammar school. She only visited her homeland again with her parents in 1962 when visiting relatives. Today she has a home in the Bavarian town of Wolfratshausen.