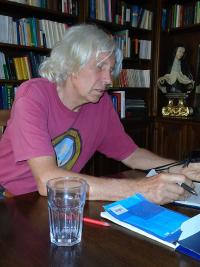

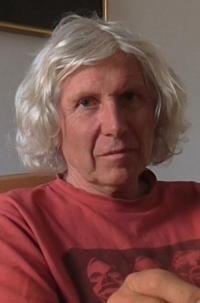

I’m just a guy who likes to model

Download image

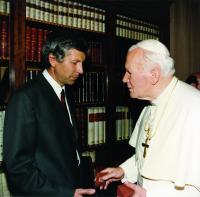

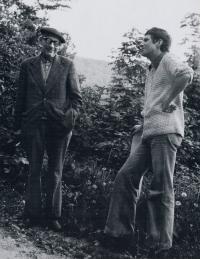

Otmar Oliva was born on 19 February 1952 to a political prisoner married to a western front veteran who was also imprisoned in the 1960s. He attended an elementary art school from early childhood. He studied sculpture at the high school of art and crafts in Uherské Hradiště from 1967 to 1972 under a major influence of his drawing teacher Vladislav Vaculka. His father left the country shortly after the Warsaw Pact invasion. In school, the witness saw the crushing impact of normalisation. He went on to study sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, graduating in 1978. He went to Greece with his future wife Olga Vrzalová, met his father, but refused to emigrate. He was actively involved in the dissent and publishing samizdat in the Charter 77 circles. The State Security monitored him and arrested him during his military service in Český Krumlov. After four months of detention, he was sentenced to 20 months’ imprisonment. Released, he married and continued to live and create in Velehrad. He created many sculptures, mostly of a sacral nature. He remained active in the dissent and publishing samizdat. He recalls the ethos of the national pilgrimage to Velehrad in 1985, which sadly did not carry over to post-1989 society. After the Velvet Revolution, he continued working in his studio in Velehrad where he casts his sculptures. He made a name for himself abroad, especially by decorating the papal chapel Redemptoris Mater.