My father, as a doctor, always carried morphine with him in higher doses. He said that if they were to go to a concentration camp, he would inject me, my mother, and himself with it.

Download image

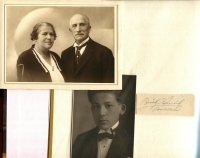

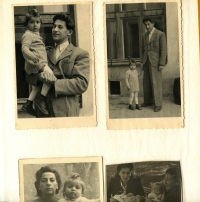

Eva Ochodničanová was born in 1942. Both her parents were of Jewish origin. Her father Ján worked as a doctor in Fridman, a town in the Tatra Mountains, which today belongs to Poland. Her mother Alžbeta was a little younger, so she did not finish her medical studies because she was expelled for racial reasons. Her father’s family - the Reizs family - also had their pub in Malacky aryanized. The family lived in the borderland, probably on an exception, which was probably provided to the father by the Ludak poet Rudolf Dilong, the partner of Jan’s sister Valéria. After the uprising, however, the family had to go into hiding, sheltered by the hermit Mieczysława Faryniak. Eva was hidden by the widow Helena Sowa, who had several small children. There, in January 1945, they lived to see the liberation. It was only after the war that Eva was finally able to meet her maternal grandparents, who had also managed to survive the war. Dad started practicing medicine again. Eva graduated in ophthalmology and did this work until the coronavirus pandemic arrived. Her father died in 1988, followed four months later by her mother and in 1990 by Mieczyslawa, who today the Poles want to have beatified.